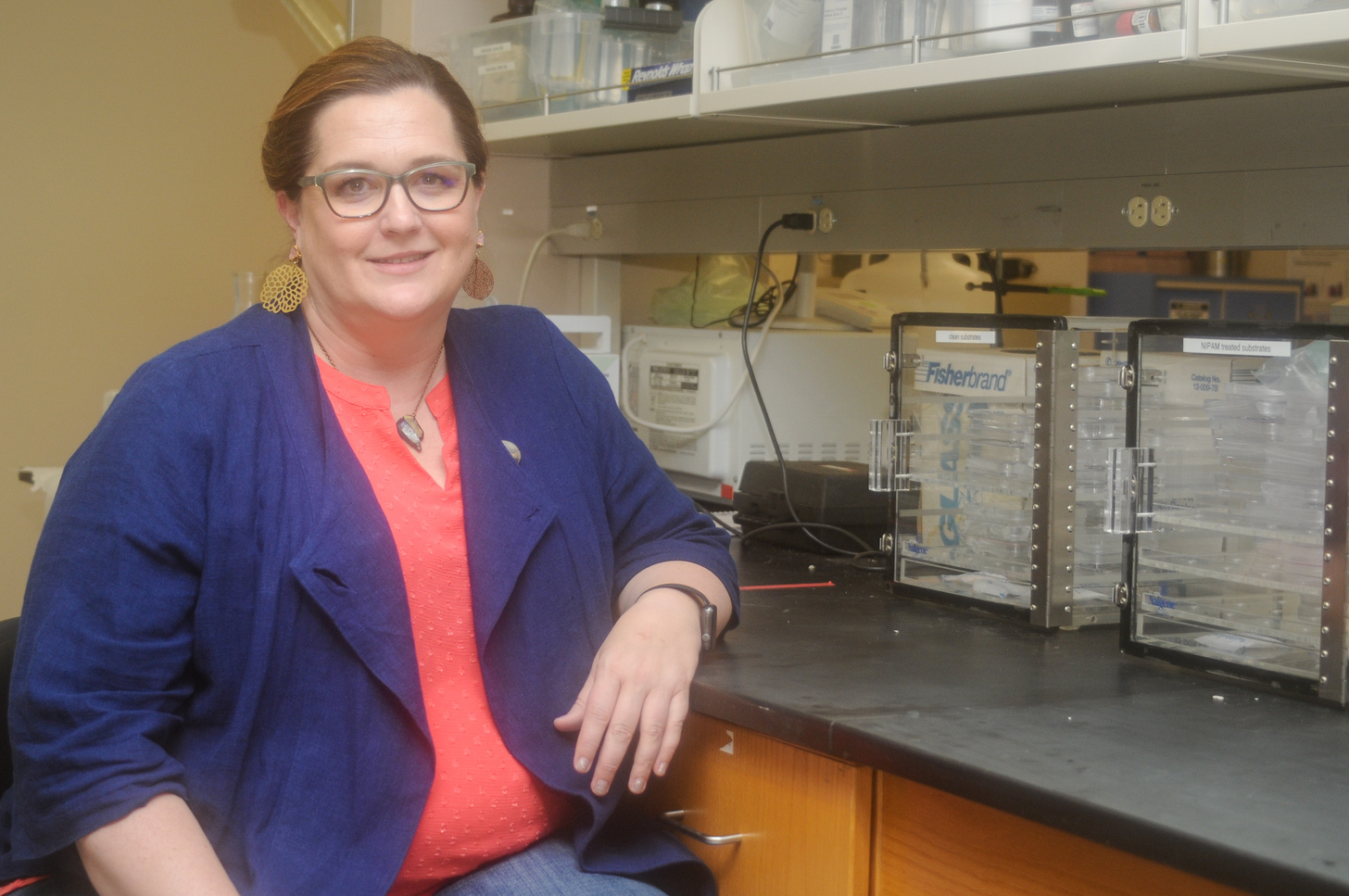

Necessity, as we’ve all heard a million times, is the mother of invention. University of New Mexico associate professor Heather Canavan’s Adaptive Biomedical Design program has taken that idea and applied it to finding ways to solve real-world problems for people with disabilities. She believes we need to break the cycle of solutions in the built environment that may be Americans with Disability Act (ADA) compliant, but not actually disability friendly. Current solutions often focus on one disability, yet 75 percent of people with a disability have more than one. To that end she has begun working with students at UNM to develop prototypes that move beyond ADA specifications to create a more accessible environment through the implementation of practical retrofitting. It’s a bold idea driven by design, and she needs your help. Weekly Alibi sat down with Canavan to talk about her work and her team’s Adaptive Design Challenge this weekend. The following is an edited version of that interview.Weekly Alibi: What is your program trying to accomplish?Heather Canavan PhD: I had a really fundamental background in research. I was interested, and the 20 people around the world that read my papers were interested, but when I was out for my cancer treatment, I realized that there are a lot of things that just aren’t very well designed. It’s because there is a lot of push in science to look at the long problem. How are we going to cure cancer? How are we going to cure Alzheimer’s disease? Those are the long reaching, overarching goals. I realized that’s mostly what I had been doing. I started thinking that there are a lot of problems that are very immediate and don’t seem quite as important. Those are the “dumb” problems I’ve been working on, but they’re not dumb when there is a quarter of the population that is going to have a disability.Where do your students come from? Do they come from the medical side? The design side?They come from all over. About half of the students in the biomedical engineering program come from biology. Johnny [Hutton] is one of the most recent students and he comes to us from the military. We have students that are coming from more traditional mechanical engineering.How do you start the design process?You just start bouncing ideas off of each other and brainstorming. Then you start thinking how you can make progress rapidly so you can test things out. We have teams of five people and I try to mix it up so there are undergraduates and graduates—people from biology with people from engineering. People that are interested in industry and people that don’t know. Ultimately, I would love it if we had people that were in the business school and fine arts so that we have a really big set of different experiences.Creative problem solvers?Yes. The example I always like to use is–if you have only one type of person in the room, you end up with cars with airbags that don’t work. My colleague next door is a full foot shorter than me–she is 4’11”–she could not use those [air]bags because they would kill her. If you have someone like that in the room, you’re going to know that you can’t put children and small woman in front of those. Let’s make it more interdisciplinary and mix it up.Are you doing virtual prototyping or are you using physical materials?It really depends on the project. The idea is that all of them (the projects) will have an actual prototype. How can the public be involved in this process?We are doing the design challenge for a couple of reasons. If people are going through these different design challenges that we’ve set up, then they’ll gain an understanding, an empathy for what it is like to have limited mobility and need to solve a challenge like how am I going to eat something if I can’t use my hands and just have a straw. Or, how am I going to back up [in a wheelchair] through a room full of Jenga-type stuff. It gives them the mindset already and then at the end they’ll give feedback on the prototypes. We don’t want to wait for a $5 million study that tells us the button [to open a handicap accessible door] is this high and it needs to be this high. We know we can fix it.

Adaptive Design ChallengeSaturday, March 30, 10am to 2pmCentennial Engineering Center, Building #112UNM Main CampusFree admission