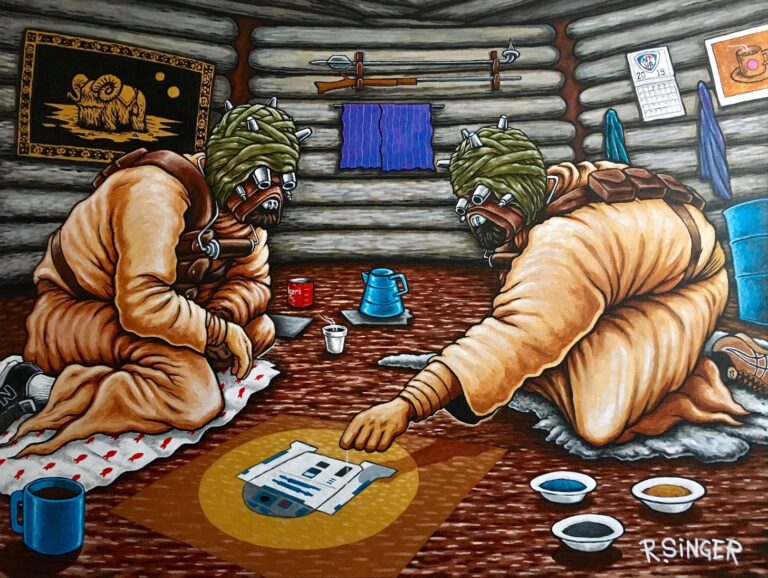

Ryan Singer’s new collection of paintings, Childhood Mythologies, now showing at Form & Concept in Santa Fe has been called indigenous futurism, but like most contemporary Native American painting, labels fail to convey the complexity of the art or the artist. For one thing, the sci-fi imagery that Singer blends with Navajo landscapes comes from the past, not the future. Specifically, his past growing up on the Navajo Nation in a Reagan-era brimming with 8-bit video games, monster movies and plastic toy versions of the same dinosaurs that once roamed that same land. The future may be as bright as his pallet for painter Ryan Singer, but the mythologies in his work can be recognized from a past not so long ago, from a place not so far away. Star Wars, with a mythology derived from the greatest hits of Western fables but a set of characters, concepts and conflicts that audiences can identify far beyond the West, are used to look at both the films and the Native landscape in a new way. Weekly Alibi sat down with Ryan Singer to talk about inspiration, myth and the healing power of art. The following is an edited version of that conversation.Weekly Alibi: Where does inspiration come from?Ryan Singer: I don’t know. I just make myself paint. I enjoy the act of creating something. It can be really hard to start from nothing because it seems like it is overwhelming, but I just get going. I just start. I go into it, play some music, get motivated and get into it. The next thing you know, it starts doing it itself. It starts becoming something. Somewhere past the middle, it starts becoming what I want it to be. Sometimes it has its own life like it is being created in front of my eyes. Sometimes it feels like I’m there physically, but I’m not there mentally or spiritually. It feels like I’m somewhere else.I’ve heard this story from other artists.It’s like your body is a vessel and it’s just doing the physical work. You’re consciously thinking about it, but it seems like you’re somewhere else. Like someone else is helping you. I think it’s like a muse, or somebody else that helps you out along the way. It is something I’ve been appreciating and realizing that it is sort of a real thing. Some people call it ‘The Zone.’ Before I used to struggle at getting at it. I used to have to really concentrate. Sometimes it would happen and sometimes it wouldn’t. But now, usually before I do a whole day of painting, I’ll meditate for 10 or 15 minutes, just clear out my mind and just sit there. Just really quiet and focus on just breathing. Letting everything go away and just relax. Then, come back and just start working. That seems to help me get right into the zone. I can pop right in there. Once it’s happening, and I can tell when it’s happening, I just let it go. I can stay in that thing all day. Somedays I’ll start in the morning and I’ll go until 7 or 8 at night. Sometimes it’s like “where did the time go?”Are you surprised by what you created the next day?I’ll see it happening and sometimes I have to step away for a while.Do you think that art can heal in a larger context beyond the individual?I think so. If they can take something out of it that they can connect with. If they can get an emotion and realize what’s happening. If they can use that and feel better about themselves. That is what I’ve always gotten out of art. Even doing drawings. If I had like a big break up or a big fight with a girl, I would run to a coffee shop, get out my sketchbook and start drawing. I would be so upset or mad, but I would take out my sketchbook, start drawing and let it come out through my artwork. The next thing you know, I’ve got this bad ass drawing. Then I feel good. It’s not as bad as it could be. I could just go mope around, and be all bummed out or cry about it. I always use the art to escape and cheer myself up.In your piece (De)Colonized Ewok, you’ve taken a mythology from Star Wars and used it to show the impact of colonialism on an individual from a different, fictional native culture. It’s a parallel with the US and what they did to Native Americans. It not only happened here, but it happens all over. It happens in New Zealand and Australia. The layers of meaning can fluctuate. There’s the Star Wars level. There’s the level of the movie. There’s the level of indigenous stuff and there is the level of genocide and colonialism. With your piece As Adults, We’re Still Children, you have replaced the barnyard images on the Fisher Price See ‘n Say with images of mythological creatures. Why do we talk about these things?We still haven’t figured out everything. We have so much science and technology, but we still can’t find Bigfoot. We still don’t know what happens after you die. We don’t know if there are ghosts or not. We don’t know if there’s a Loch Ness monster. We don’t know if people get abducted. There are so many accounts it’s like “what’s really happening?” Is the government hiding everything that we can’t see? It gets really complicated and there’s so many things we don’t know. I think that saying these things don’t exist is stupid. The brain needs a way to contextualize what you’ve seen and heard.I think it would be pretty boring if everybody knew everything. I don’t think we’ll ever get to that point.No. I think we’re going the other way.

Childhood MythologiesPaintings by Ryan SingerThrough May 25Form & Concept Gallery435 S. Guadalupe St.Santa Fe