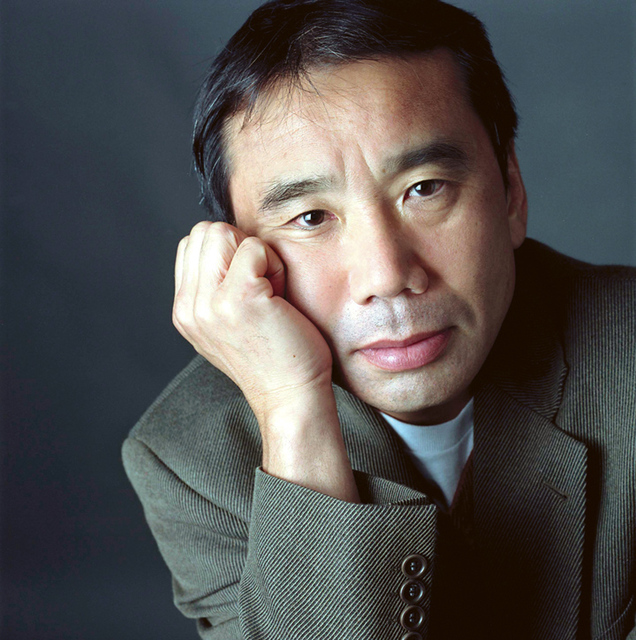

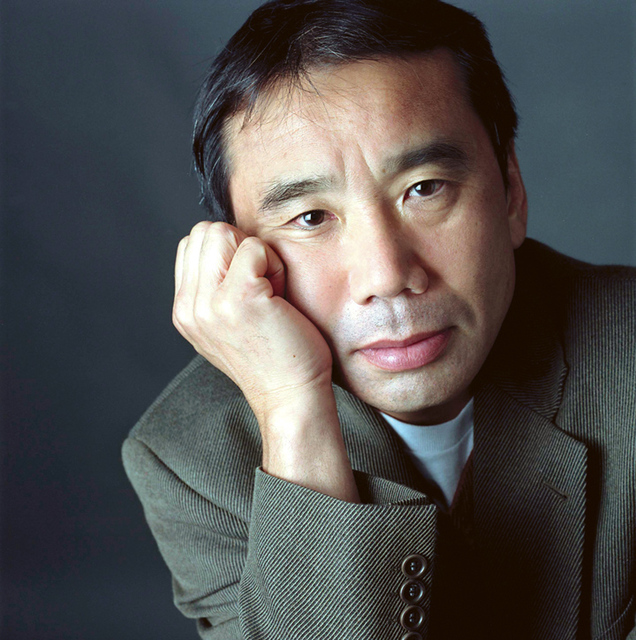

Some people have epiphanies in church, others atop mountains. Haruki Murakami‘s came on April 1, 1978, on the grassy knoll behind Jingu Baseball Stadium in Japan. What if he tried to write a novel? Thirty years and nearly three dozen books later, it’s clear that Mr. Murakami answered the right call. His strange, wonderful novels, from A Wild Sheep Chase to After Dark , are cult hits the world over, translated into 48 languages. But as he describes in his new memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running , this burst of productivity would have been impossible were it not for the simultaneous arrival—those many years ago—of another epiphany, an unlikely one for a three pack-a-day smoker: What if he went for a jog? Sitting in the dimly lit lobby of a midtown Manhattan hotel, having already woken, gone for a run, written and conducted another interview, the energetic 59-year-old novelist explains how what started as a hunch became the organizing principle of his life."I have a theory," he says in a deep baritone. "If you lead a very repetitious life, your imagination works very well. It’s very active. So I get up early in the morning, every day, and I sit down at my desk, and I am ready to write."When he talks about his writing, Murakami sounds like an odd mixture of existentialist, professional athlete and motivational speaker. "It’s like going into the dark room," he says, his voice slowing. "I enter that room, open that door, and it’s dark, completely dark. But I can see something, and I can touch something and come back to this world, this side, and write it." He gives a long, Quaker-silence-like pause and then adds a caveat: "You have to be strong. You have to be tough. You have to be confident of what you are doing if you want to enter that dark room."Even when he is not in Japan, Murakami’s life looks the same. He wakes early, writes for several hours, runs and spends his afternoon translating literature. He has translated The Great Gatsby , Catcher in the Rye and, most recently, Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely .The patterned nature of his days could not be more different than those of his characters, however. Murakami writes of people blown sideways through life by chance or freak circumstance. Kafka on the Shore features talking cats. After the Quake includes a story about a man who believes a giant frog is taking over Tokyo. In some ways, though he has a routine, Murakami knows how fate can change a life. Two events outside himself have made a large difference on his own. The first came in the late ’80s. Tired of what he called "the drinking and back-scratching" of Tokyo literary society, of which he was an outsider, he left the country and wrote a novel, Norwegian Wood ."It sold very, very well—too much," Murakami says, laughing: "Two million copies in two years. So some people hated me more. Intellectual people don’t like a best-seller." Murakami stayed away more, moved to America; and then 1995 came.During that year, Japan suffered a financial meltdown and a terrorist gas attack on its subways. Murakami came home and spent a year listening to the voices of the survivors. He ultimately channeled them into the oral history Underground .The experience changed him and how he wrote characters. "You know, many people don’t listen to the other people’s story," he says. "Most of them think other people’s stories are boring. But if you try to listen hard, their story is fascinating."Since then, Murakami has not only written characters differently—he opens the window, as he puts it, now and again. For two months out of the year, he answers readers’ e-mails. "I just wanted to talk to my readers," he says, "listen to their voices."And then he shuts it. His determination to write still vibrates off him in waves. He wants each book to be different, better than what came before. He just finished a mammoth novel, "twice as long as Kafka on the Shore ," he says, about horror, which will be published in Japan next May.In the meantime, he doubts another epiphany will come. "I can remember what it felt [like]," he says about writing his first book. "It’s a very special feeling. But I guess once is enough. I think everybody gets that epiphany once in a lifetime. And I am afraid many people will miss it."

John Freeman is completing a book on the tyranny of e-mail.