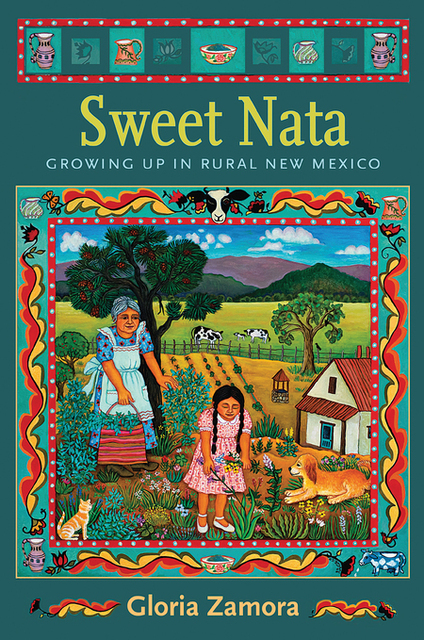

Because Gloria Zamora is one of my own former writing students, Sweet Nata ’s publication gives me special joy. But despite the thrill of seeing her memoir in print, it’s been a difficult winter for Gloria. Only five months ago, Mike, her husband of 33 years, died suddenly while cutting wood in the Jemez. Still stung by this loss, Gloria chose not to change her biography on the back of the book; it states that she lives with her husband in Corrales.Even before Mike’s death, Sweet Nata had a bittersweet tinge, and Gloria knew early on that she wanted to give her memoir a half-English/half-Spanish title that would convey this. Gloria peels away her childhood one brief tale at a time, with an unstinting honesty that not only brings her family to life but immortalizes each of its individuals.Gloria says she wrote Sweet Nata for her grandchildren. “I remember my father saying things like, ‘I’m telling you guys this because I don’t want you to forget it,’ ” she notes. “I wrote [the book] to keep his stories and mine.” As a toddler, Gloria was sent to live with her grandparents on their ranch outside of Mora. “[My parents] lived in that little trailer [in Corrales],” Gloria explains. “They’d sent my brother Tony first, but my dad was so sad he’d sent his first boy, and my mom was so sad she’d sent her first-born, so Tony came back,” and Gloria went instead. Not that this was an easy choice. “I was sent mostly out of necessity,” Gloria says. It wasn’t until many years later that her mother, Irene Tafoya, told her this was a fairly common practice for Hispanic families, and that she and her own cousins had moved among various aunts and uncles when she was growing up. Sweet Nata not only re-creates Gloria’s grandparents’ ranch for the reader, it brings her grandparents back to life as well. “ ‘ Tejaván ’ was one of my favorite sections to write,” Gloria says. “I wanted to show how Grama was—loving—and that she had depth, too. Grama was a worker who also showed her spiritual side.” Gloria is also especially fond of the section “This Little Piggy,” which details a matanza (a pig roast that begins with the slaughter of the pig). “A lot of people—yeah, like you—go eew , but it was fun to write. I tried to make it a little lighter so that people wouldn’t get turned off by it. Matanza was always like a fiesta for us, a big old family gathering where everyone eats and eats and eats and laughs and jokes.”One other section Gloria calls out is “Kindred Spirits,” about her best friend Kathy, who was just the person she needed when she moved back from Mora: “We were … made for each other,” Gloria says, laughing even now. “All the way to school we’d sing, and then all the way home, just making up songs. It made me happy then and it made me happy again when I wrote about it.”Northern New Mexico painter Diana Bryer created the painting on the cover just for the book. “There was so much I wanted in it,” says Gloria, “and she got it all in there. My Grama’s apron. Her hair, always in a bun. My braids, me picking flowers. Chulo, the dog, and the cows in the fields. The well. A piñon tree. There were so many things, and they are all there.”Like its cover, Sweet Nata packs a lot of detail into each of its vignettes. Weddings, funerals, matanzas and harvests provide intimate glimpses into the daily struggles and triumphs that turn a family into a community. “Family needs to be there for each other,” Gloria tells me. “Anything that needs to be faced, if your family is there to support you, you can face it.”

Gloria’s family will be out in force for the four events she’s scheduled thus far: the National Hispanic Cultural Center on March 28 at 2 p.m.; Bookworks on March 31 at 7 p.m.; the Corrales Community Library on April 15 at 7 p.m. (and where she’ll also accept this year’s Red Shoes Award, given in memory of the late community activist Dara McLaughlin for courage in writing); and at Tome on the Range in Las Vegas on May 9 at 3 p.m.