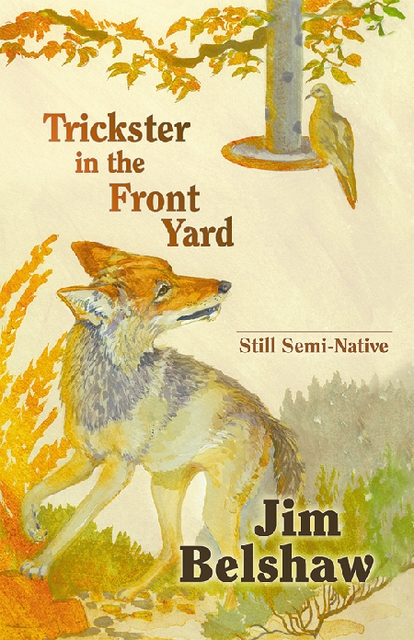

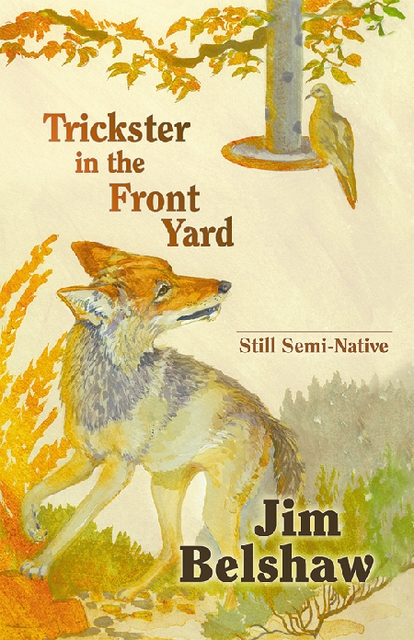

A few weeks after Jim Belshaw left the Albuquerque Journal, he found himself reflexively pulling pen and paper from his pocket. "What are you doing?" his wife would ask. He still sees potential columns in the people he meets, in snippets of conversation.The most common question for a columnist, Belshaw says, is, How do you come up with your ideas? He says Andy Rooney put it best—when you sit down and look at the clock and there’s two hours until deadline, you damn well decide to have an idea.Before Belshaw knew he would retire from thrice-weekly column work, he found himself in the library, digging through his last 10 or 15 years’ worth of material. That’s just a fraction of his output. Over the course of 28 years, he estimates that he penned in the neighborhood of 5,000 columns.As Belshaw sifted, a few shook loose. He’s compiled those into his second collection, Trickster in the Front Yard: Still Semi-Native. He doesn’t recall favorite articles as much as he does favorite people. Like Milton Hancock, a man awaiting a heart transplant for more than a year at Presbyterian who became the hospital’s de facto Navajo translator. Or the 83-year-old woman in Willard, N.M., who invited Belshaw over for coffee to talk about poverty. When Belshaw entered that tiny kitchen in Valencia County, the woman opened with: "I hate winter. It reminds me of when I didn’t have shoes"—a stunner of a first line. "I thought, Oh boy, this is going to be a good one," he says. The stories people have to tell aren’t just good, he finishes; sometimes they’re profound.Though he looked primarily for non-newsmakers—that is, people you wouldn’t normally see in the daily news world—he also found stories by "staying in the room." For instance, he wrote about a 29-year-old scientist who was attacked in an alley in 1996. He spent three months in a coma. Belshaw got close to the family and spent nearly a year telling his readership about the ripples of that beating. Column after column, he followed the scientist’s recovery—and the sad fact that the brain damage was permanent. "I was doing something newspapers usually don’t do and usually can’t do," he says. "I was hanging flesh on these people."Being a columnist made Belshaw a public figure, he says. Readers skip right over bylines, and "newspaper reporters are by and large anonymous." But once a writer begins using the dreaded first-person pronoun and includes a photo portrait at the top, people take notice. Belshaw says he routinely got phone calls from readers who were upset about something someone else wrote. They knew he wasn’t the person who wrote the article. Still, they’d say, You’re the only person at the paper I feel like I know.He acknowledges that there’s a great deal of ego involved in being a columnist. When Belshaw first started, he says he wanted to be Albuquerque’s Mike Royko, a Chicago writer who "didn’t write columns as much as he punched people in the nose," he says. "He was very smart and very tough and very hard”—the kind of guy you love to read but who you’d never want to be in the same room with. It didn’t take long for Belshaw to figure out that God only made one Mike Royko, and that guy lived in Chicago. Belshaw wasn’t cut out to write the brutal stuff. Instead, he calls his style "conversational," more entertainment than news. "I was good at writing funny stuff," he says. "Well, it depends on who you talk to. Humor is hard. A certain percentage of people won’t get the joke. Another percentage won’t like the joke."Belshaw brings up the fact that years ago, the Alibi named him one of the five worst people in Albuquerque; an anonymous writer eviscerated him as being completely unfunny and without a single socially redeeming value. "It was the job of the alternative newspaper to take down the big guys," he says. He remembers the days when a newsroom was full of shouting, ringing phones and the chatter of wire machines. A tobacco haze hung in the air. "Everybody smoked," he says. People would ask him how he could work with all that noise. "And I would say, What noise?" These days, everything’s computerized, he says, and quiet. E-mail, in particular, changed the game. "I’ve had people say things to me and call me names that they would never dream of saying to my face or on the phone," he says. But Belshaw says no matter what, he prided himself on answering nearly every e-mail. The Journal is constantly modifying itself, he says, to find the magical formula that will stop the terrible slide daily newspapers are experiencing. As part of one such change, Belshaw says he was asked to help set up photographs that reflected the subject matter of each of his columns. An old back injury from a motorcycle accident prevents him from being on his feet for more than 10 or 15 minutes. So rather than continue at the paper, he decided to do something different. "My very dear friend Tony Hillerman used to say it was a good idea to re-pot yourself." There’s a great American novel on his mind, one he has to finish and get out of his system. But it’s bad luck, he says, to talk too much about its contents.Belshaw says leaving the Journal isn’t sweet or even bittersweet. "I’m just kind of all right with it," he says. "It was a good, long ride."