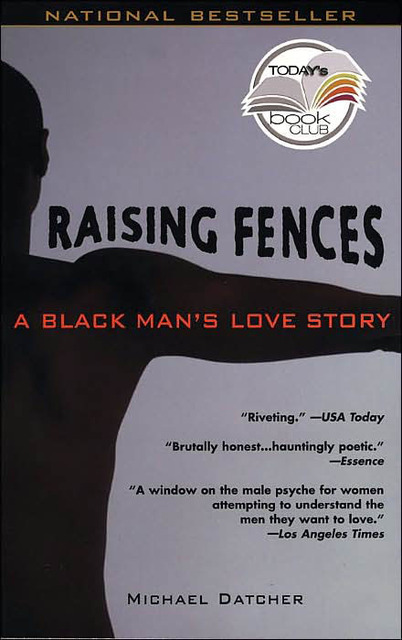

Los Angeles-based writer Michael Datcher has a roving eye, at least as far as genres are concerned. He’s equally enamored with memoir, fiction, poetry and journalism and refuses to commit to just one. His 2001 autobiography Raising Fences: A Black Man’s Love Story was featured as part of the Today Show Book Club series and caught the eye of none other than Dame Oprah. Raising Fences chronicles Datcher’s childhood growing up fatherless, given up by his birth mother for another woman to raise. It takes a naked look at how black boys become black men often without any men around. It’s a cycle that Datcher hopes, through honest examination, will be broken.While honesty was always a goal of Datcher’s in composing Raising Fences , he admits that the earliest draft wasn’t as raw as the book turned out to be. "I focused on what a great guy I was, all the incredible things that I’ve done and I’m such an awesome guy," he laughs. But that wasn’t cutting it. He knew he had to lay himself bare in order to hit at the essential truths he wanted to communicate; he’d have to explore both childhood trauma and the regrettable moments of his adult life. Doing so wasn’t easy. Just as the book was about to come out, he says, "I thought, I cannot publish this book, it’s gonna be terrible. I was so afraid of speaking these things out loud that I was physically ill. I was a mess." In addition to highlighting the difficulties of his childhood, Raising Fences also talks about how Datcher himself was in danger of becoming an absentee father, despite his deep desire to discontinue the cycle of abandonment. So, for his first reading in New York City, he says that he not so much read from his book as performed it. “Tooo-daaaay, as I walk down the streeeeeet,” Datcher calls out, remembering his overdramatism. “People were like, what is he doing … ? It was insane, it was crazy. I had to create some kind of buffer. I was so terrified of saying those things."But it’s precisely because of what Datcher calls his book’s "vulnerability" that his audience feel as if they know him. Which they often come up to tell him, and which, he confesses, he hates. "That book is not me. I’ve undergone personal growth. I’m beyond that." But he acknowledges that the issues the book raises are of vital importance to the African-American—hell, the American—community, and the recognition he’s received as part of the book’s success has enabled him to become a heeded voice in the discussion about black men and their families. The title of his memoir brings to mind the August Wilson play Fences, about a rural African-American family struggling to maintain a cohesive and funcitonal unit while a changing social structure threatens to undermine it. He grants that there are parallels. "Wilson’s play is about father and son relations, and my book is about fatherlessness and the complicated nature of trying to raise a family in the context of black people’s experience in America." But he says that Wilson’s rural characters have a different set of issues than those of Datcher’s own urban upbringing. "Many young black men are growing up with fatherlessness … many young black men are learning fathering from the streets, and those models are not healthy." He sees that men make choices to emulate the “playas” around them rather than choosing to be the fathers they’ve never known.But changes are happening, including the installation of the first African-American family in the White House. All of America now has as its first family a unified black family, led by a man who was himself fatherless. "When you’re young," Datcher says, "you want to be cool. Being cool is being a playa, a ladies’ man and everything. Pimp. But now the president, who is a cool guy, who has a cool personal style, is living with a black woman, has redefined what it is to be cool. That is amazing." The impact won’t happen overnight, but it is happening. One of the things he hopes changes, in part because of work like his and the example of the Obamas, is the image of black people in popular culture. They’re put into boxes, and the influence of hip-hop as the predominate representation of black culture is a big part of that. “If you don’t fit that [hip-hop] model, people say you’re not ‘authentically black,’ like there’s one fucking definition of black people."The novel Datcher’s working on touches on rigid delineations, exploring race as a construct. Titled The Eunuch , it follows a mortician’s twin sons, one of whom has vitiligo, a skin condition that causes depigmentation of the skin. Set against the horror of the 1917 race riots in East St. Louis where approximately 100 African-Americans were killed, Datcher raises the question of what race means; for someone who has vitiligo, "What does it mean to be black when you’re white?"He’s not the first to tackle these issues, and Datcher gives special credit to the influence of author James Baldwin. The Fire Next Time was, Datcher says, "for me, the first great memoir." He describes it as a profound rumination on "race and politics and power in America." Reading it proved to be a pivotal experience. "That book is so unbelievably powerful. I was spellbound. I thought, Wow. If reading a book can impact me like this, I wanna do what he’s doing." Datcher at one time had every intention of going into business, but work like Baldwin’s veered him onto a different path. "Art literally changed my entire life," he says, and through writing, it’s his hope to do the same for others.

Michael Datcher will be in Albuquerque to read at the Outpost Performance Space (210 Yale SE) on Saturday, May 9, at 7:30 p.m. as part of the 516 ARTS exhibition West Southwest: ABQ-LA Exchange. Also reading with him will be locals Maisha Baton, Hakim Bellamy and Idris Goodwin, with a spoken word duet about Charles Mingus performed by Virginia Hampton and Stephanie Willis. Tickets are $12 general, $10 for Outpost members and are available through 516 ARTS(242-1445). See 516arts.org for more.