Author Interview: Legend Max Evans On The Landscape Of Western Writing

Literary Legend Max Evans On The Landscape Of Western Writing

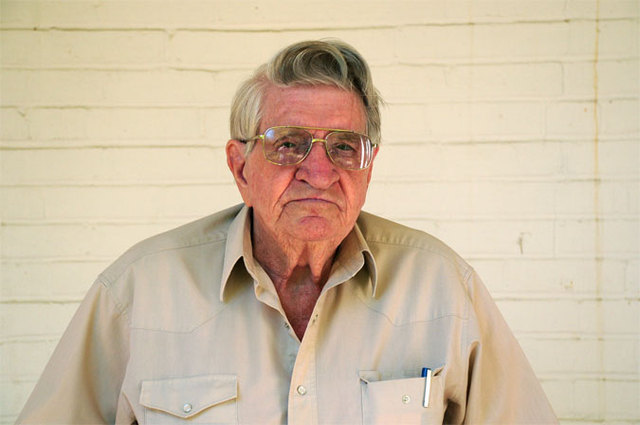

Evans has lived in his Nob Hill home nearly half a century.

Photo by Sam Adams

Max Evans was the subject of a panel event ("Coffee and Hot Biscuits with Ol' Max Evans") on June 14 that honored the author and his oeuvre. Evans is pictured here outside his Nob Hill home.

Photo by Sam Adams

Sam Adams