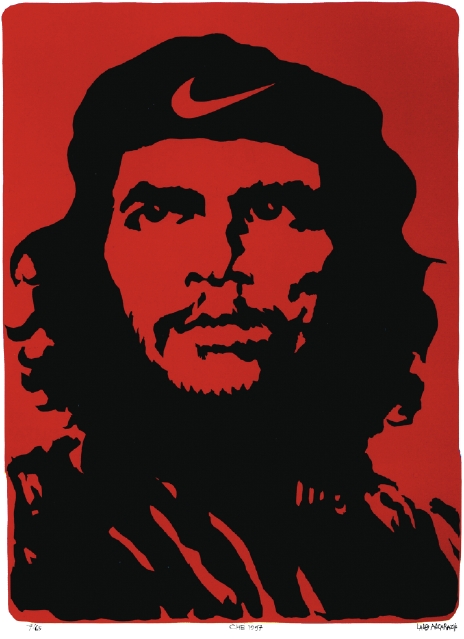

On New Year’s Day 1994, in the jungles of Chiapas, Mexico, a revolutionary group no one had ever heard of launched a highly conspicuous revolution. Calling themselves the Zapatistas—after the famed Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata—the group proclaimed to the world its outrage over NAFTA, the recently passed trade agreement that they believed would make Mexico’s poorest citizens even poorer.What the Zapatistas lacked in weapons, they made up in technological savvy. Led by a messianic spokesman named Subcomandante Marcos, the group launched a simultaneous propaganda campaign over the Internet that has since become a model for revolutionary and mainstream political groups worldwide.The Zapatistas’ campaign also made exhibits like this one at the National Hispanic Cultural Center seem quaint. Spewing propaganda these days is easier than ever. All you have to do is sit down at your keyboard, and you can jabber away to the entire world.Back in the old days—say, the early ’90s—you had to work a lot harder. Given its colorful political history combined with its rich tradition of public art, it’s no surprise that Latin America produced some of the most stunning examples of that archetypal propaganda tool: the political poster.The posters included in the National Hispanic Cultural Center exhibit largely come from the Sam L. Slick Collection of Latin American and Iberian Posters at UNM. The show also includes a few samples of work from U.S. artists. It’s quite an astonishing selection of work, and it frequently transcends the jingoism and clichés normally associated with left-wing political movements.Even when that isn’t the case, this work is fascinating. Most of the pieces in the exhibit aren’t that old, but they seem like genuine antiques because of the technological innovations we’ve seen in 21 st century politics.It’s no accident, for example, that Alberto Korda’s hugely famous photograph of Ernesto “Che” Guevara shows up again and again here. A panel in the exhibit claims that this image of the handsome Argentine revolutionary might be the most reproduced photograph of the 20 th century. It’s not that hard to believe. U.S. artist Lalo Alcaraz supplies a brilliant commentary on the overcommercialization of that image. His poster from 1997 removes the commie star from Che’s beret, replacing it with the Nike insignia.A lot of work in the show comments on commercialism. Esther Hernandez’ “Sun Mad” poster—replacing the cheery Sun Maid with a skeleton to protest the use of pesticides in agriculture—is one of the funnier ones.Some of the artists who present the most ridiculous messages do it in a way that’s visually brilliant. Take Cuban artist Luis Alvarez Mendoza’s 1973 poster of a playing card king, sword in hand, ornamented with swastikas instead of hearts. One face has been replaced with Nixon’s. The other with Hitler’s. The concept is absurd, but the image itself is breathtaking.Another Cuban artist, Rafael Enriquez Vega, has one of the most unintentionally ironic posters in the show. It depicts an attractive Latin woman with a machine gun. The title is “El Salvador: We Make War to Win Peace.” Doesn’t that sound familiar? Seems I’ve heard that same statement somewhere recently …The boilerplate lefty politics of both the work and the accompanying notes can get a little annoying. For example, one panel describes Cuba as having a stellar health care system and the best literary rates in the Western hemisphere, which is at least partly true, but the writer glosses over the dictatorship’s long record of human rights violations.These are minor complaints, though. The purpose of this show is to celebrate the artistry of this dying (dead?) form of political propaganda, and the exhibit achieves this goal magnificently.

Latin American Posters: Public Aesthetics and Mass Politics runs through March 2007 at the National Hispanic Cultural Center. For details about accompanying screenings and lectures, go to nhccnm.org. 246-2261.