The day after 9/11, I hung a U.S. flag from my dorm room window like so many of my fellow Americans. As I finished tacking it up, a man with a digital camera asked if he could take my picture. I agreed, and the next day my image was seen across the nation in USA Today .My minor celebrity isn’t the story—it’s the response I received from two federal inmates. I didn’t open the first letter; the UNM police took it to scan for anthrax. They found nothing. I felt ashamed. The second one I opened, and the letter inside thanked me for proving that my generation still felt pride in our nation. He sent a simple thank you, and I received a new outlook on those who are incarcerated.When I visited Sol Art’s newest gallery show, La Puerta de la Pinta , each artist reminded me of the author of that letter—a faceless name with a voice to be heard and time to tell a tale. Tremendous time and skill went into the artwork hanging in La Puerta de la Pinta . It would be a travesty to think these artists were discovered only because they’re incarcerated. From piece to piece, there is something masterful and intriguing about each.Consider this: Cloth is a common canvas for much of the work. Cloth canvas is often used for painting, but not for pencil or ink drawing. Think back to middle school when drawing elaborate designs or writing music lyrics on your jeans was the thing to do. Now think about trying to draw the soft features of a young woman encompassed with grief on a back pocket with a ballpoint pen. It’s only possible with the meticulous precision of a surgeon, the skill of a fine art painter and seemingly endless amounts of time.There seem to be a few common themes here. Religion and family pride are the most obvious, with heritage and love not far behind. Then there are the eyes. From many spaces throughout the gallery, sets of deep, sad, passionate eyes stare beyond the paper or cloth on which they were drawn, leaving no doubt what message the artist is trying to convey. In Jerry Zuniga’s “ New Mexico ,” an indigenous Mexican woman stares with fiery tears flowing from her eyes. The emotion locked in her face is enhanced by the red paper on which it’s drawn with black ink. The detail is so precise, I could see every strand of her hair as well as faces hidden within the folds of the snake along the border. As complex as the piece is, the woman’s eyes hold it together with intense sorrow.Just below Zuniga’s woman in red hangs Abel C. Miranda Sr.’s haunting “ Dolor es Amor” (“Pain is Love” ). The sense of urgency and impeding peril isn’t conveyed through the eyes of the man and woman depicted in this piece but in the howling ghoulish faces and skulls rising from the earth. It’s a love story—a man carrying a woman though the pits of hell on Earth—but this story leaves many things untold, which is perhaps its most romantic feature.Straying from lost love, Aaron Martinez turns the focus of the show to heritage with his untitled graphite on cloth piece. Hidden in the bushes, two Native Americans sit and watch as two conquistadors survey the landscape of the New World. The pyramid in the distance places the scene deep in the heart of Mexico, but it could easily have taken place anywhere the Spaniards invaded.Closing out the small show are two empty frames. Their placards read, “Female artist whose art was confiscated by the NM prison system.” What a tremendous loss. I can’t imagine what would constitute having your artwork confiscated while serving time in the big house. No joy for the condemned, it seems. Or maybe that’s not quite right. I did find a colored pencil drawing of Winnie the Pooh, staring down at me with happiness in his eyes.

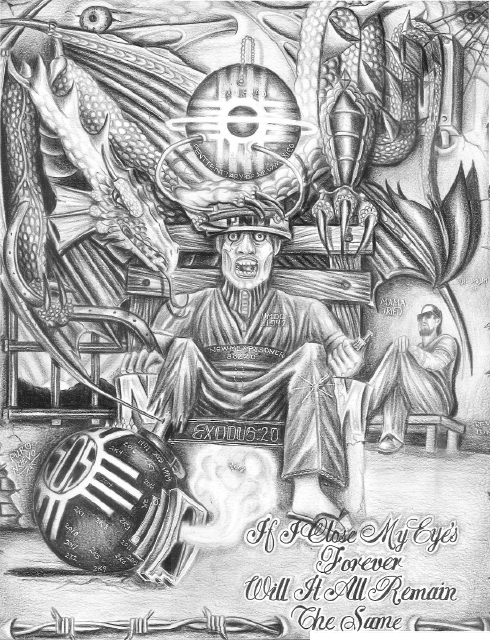

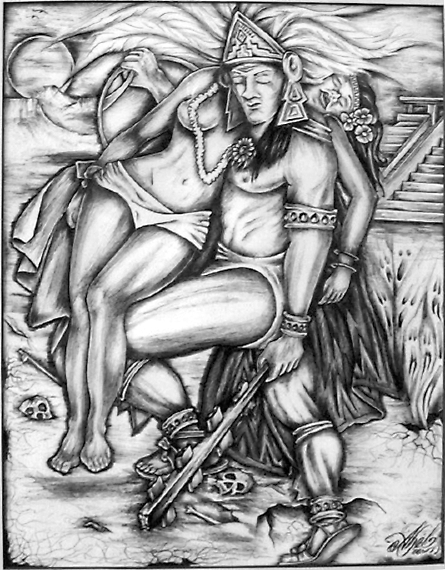

La Puerta de la Pinta , the works of incarcerated artists, will show at the Sol Arts Gallery through Nov. 26. For more information, visit www.solarts.org.