Bookstore Events

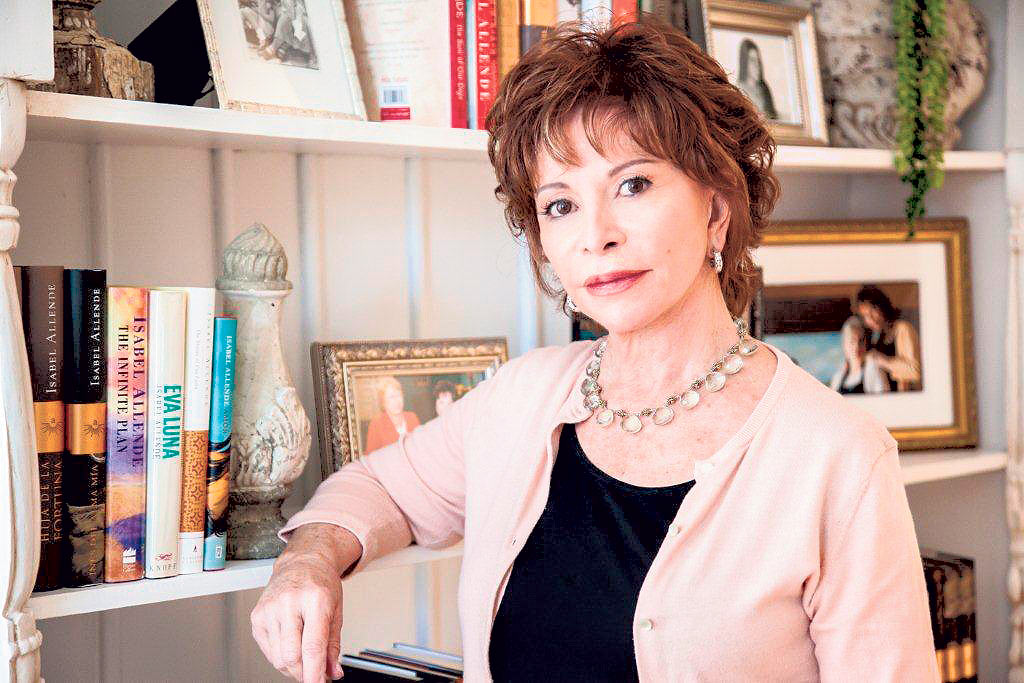

A Conversation With Isabel Allende

Isabel Allende

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Isabel Allende