Culture Shock: Grabbing The Mystery

Garo Antreasian Illuminates His Life And His Art

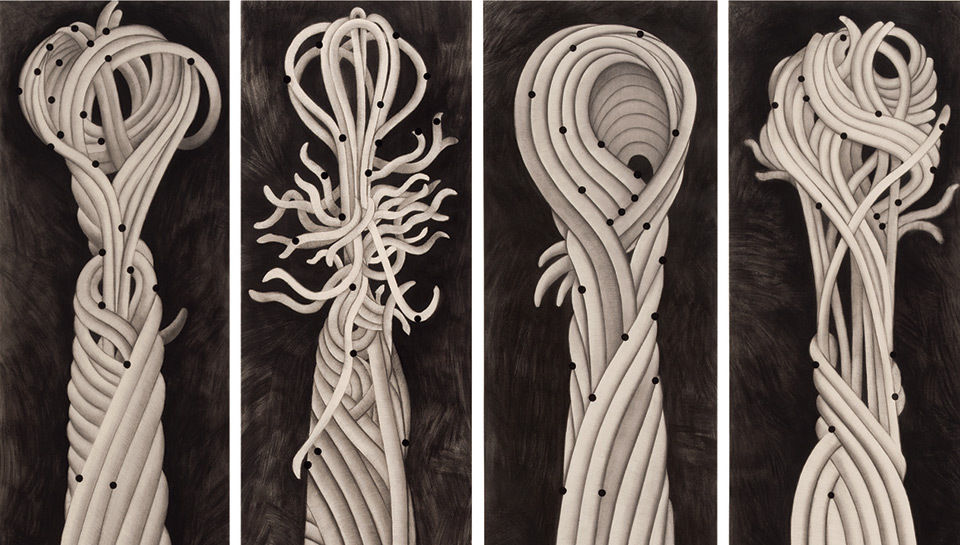

Silver Suite,Plate 4x

Garo Z. Antreasian

Garo Z. Antreasian