Culture Shock: Land Bridges

Land Art Students Forge Connections Between Species, Places, People

“Tinaja” by Erin Gould

Courtesy of Erin Gould

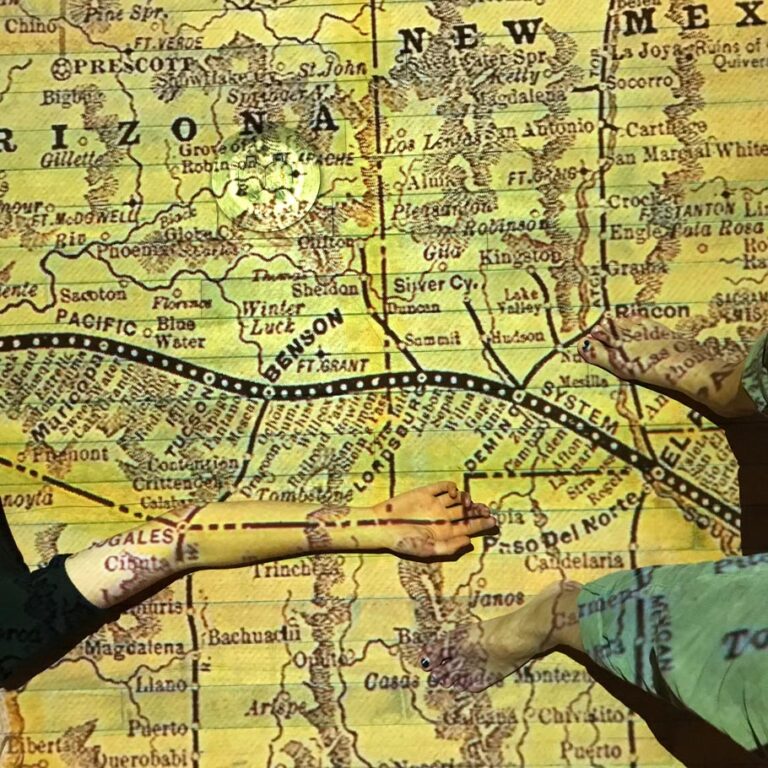

“The Land is Unstable and so are the Maps” by Jessica Zeglin, nicholas b. jacobsen and Erin Gould.

Courtesy of the artists