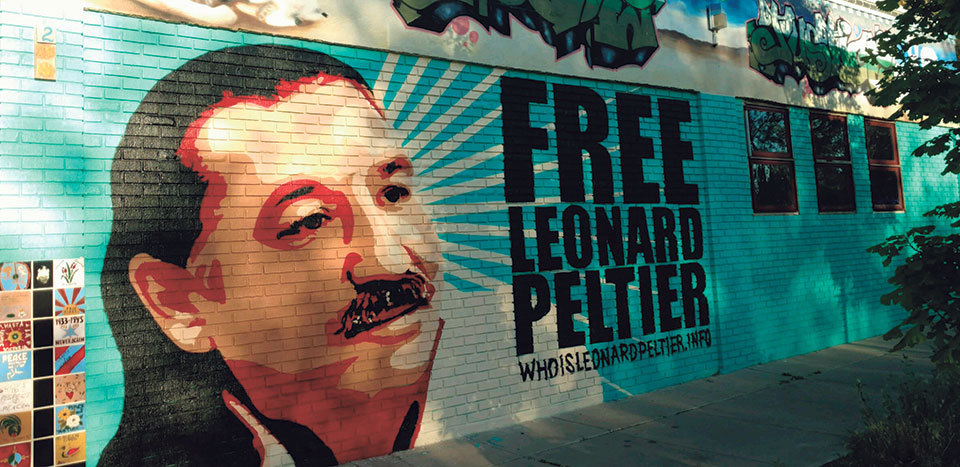

Culture Shock: Leonard Peltier’s Last Chance For Freedom

Gregg Deal's Visual Activism Is Indicative Of The Power Of Art

Dirty Velvet

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Dirty Velvet