Culture Shock: Returned To The World

Craig Childs' Latest Book Explores Pre-History And What It Means To Modernity

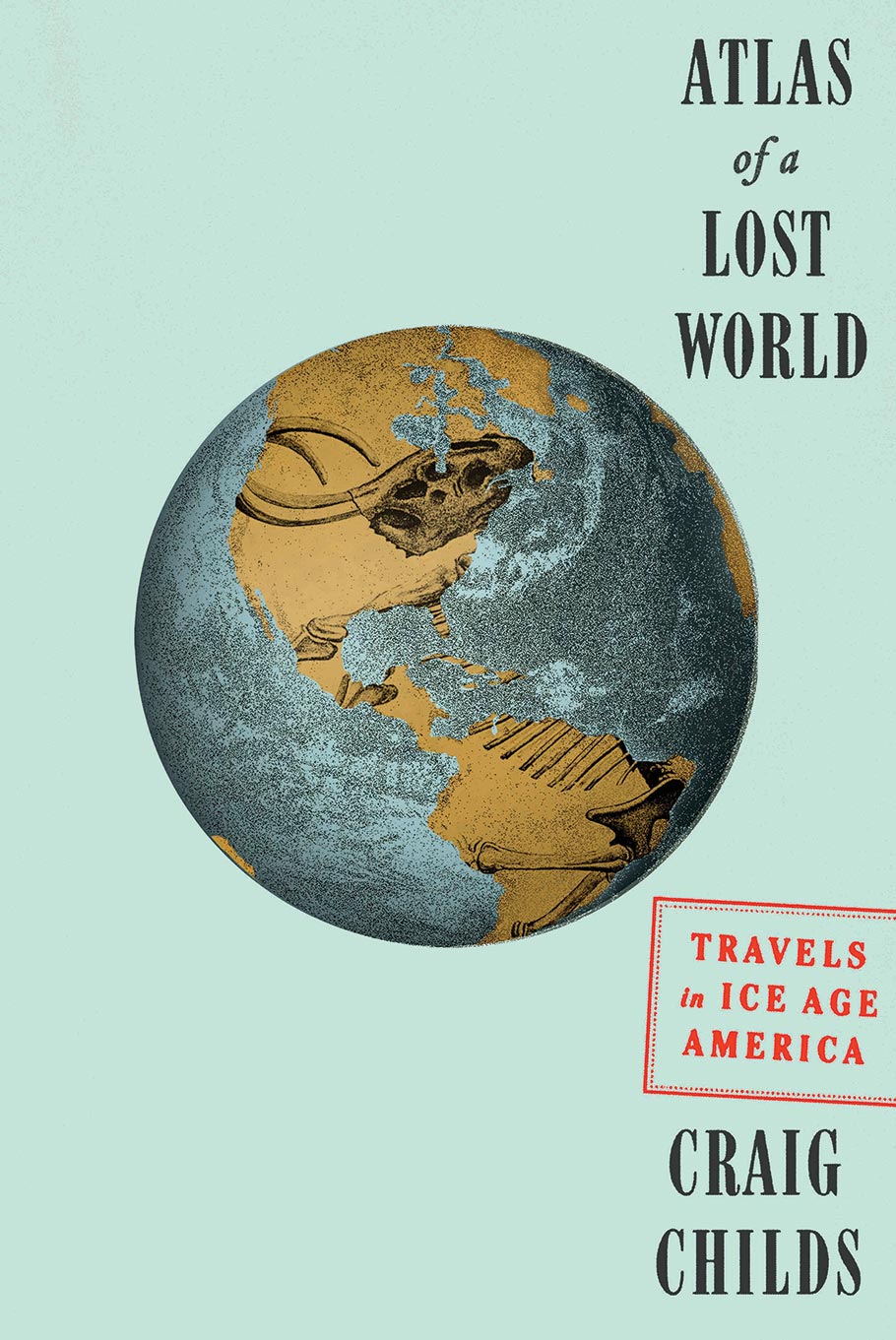

Author Craig Childs aims to let us back out into the wider world in Atlas of a Lost World