Culture Shock: Stories Never Die

Doña Sebastiana Rides On In The Work Of Ray John De Aragón

Ray John de Aragón, author of numerous books on New Mexico’s ghost stories and dark lore

Courtesy of Ray John de Aragón

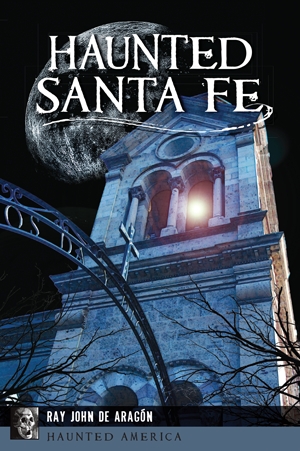

Ray John de Aragón’s latest offering is Haunted Santa Fe.

Rosa Maria Calles