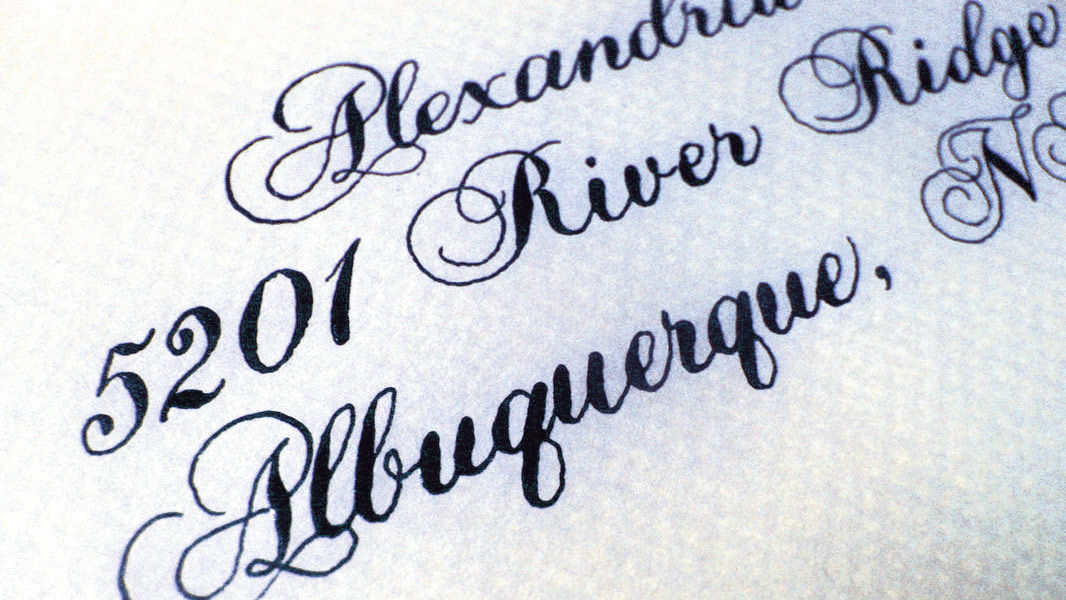

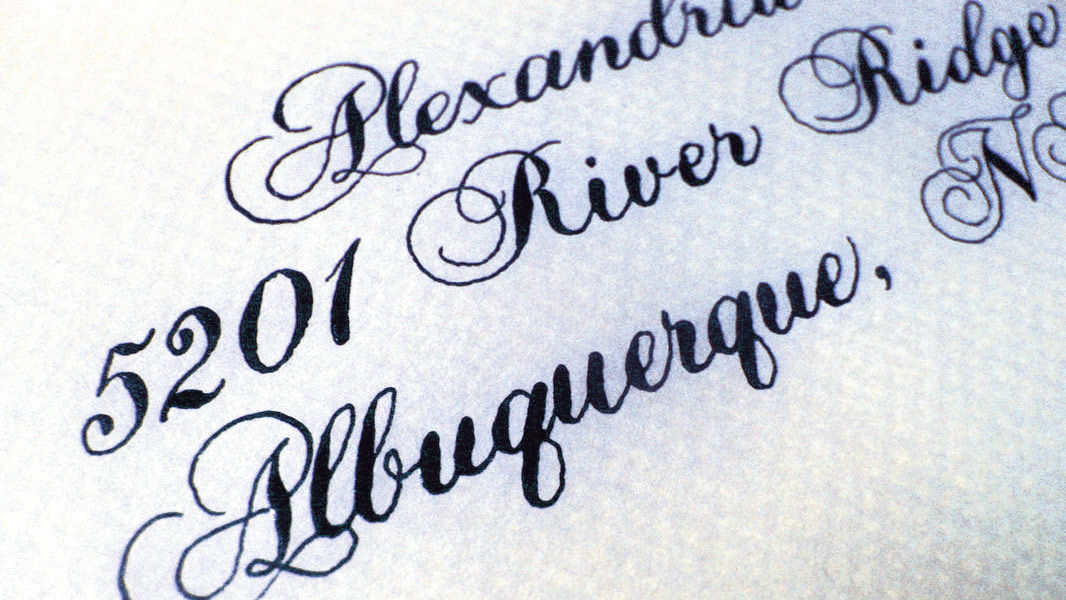

Culture Shock: The Life Of A Hand Letterer

Calligraphy Is Far From Dead At Silver Swirl Studios

Theresa Varela

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Theresa Varela