Culture Shock: The Moral Of The Ghost Story

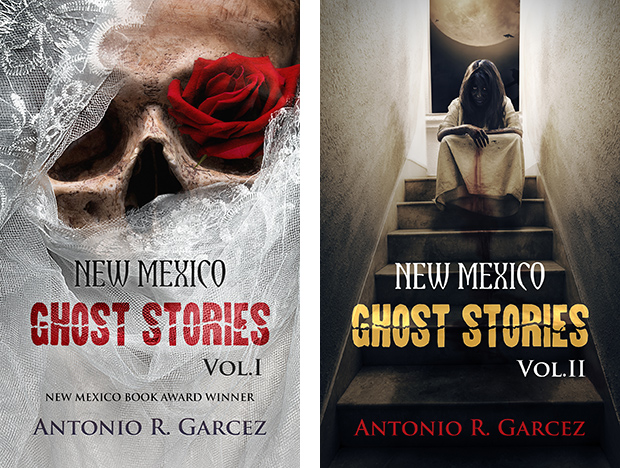

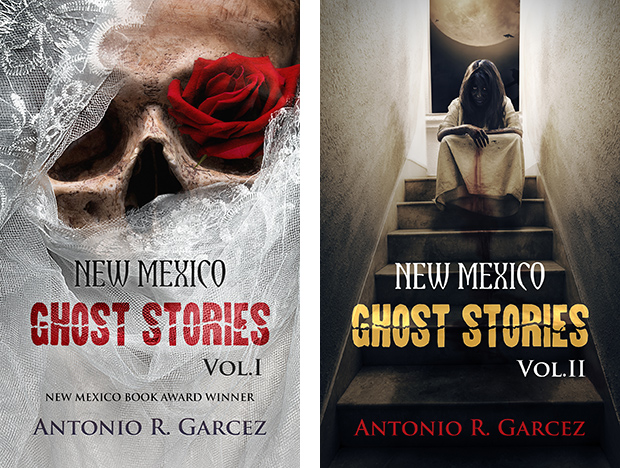

Author Antonio R. Garcez On Ghostlore And The Undeniable Substance Of The Supernatural

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992