Culture Shock: The Muscle Of Memory

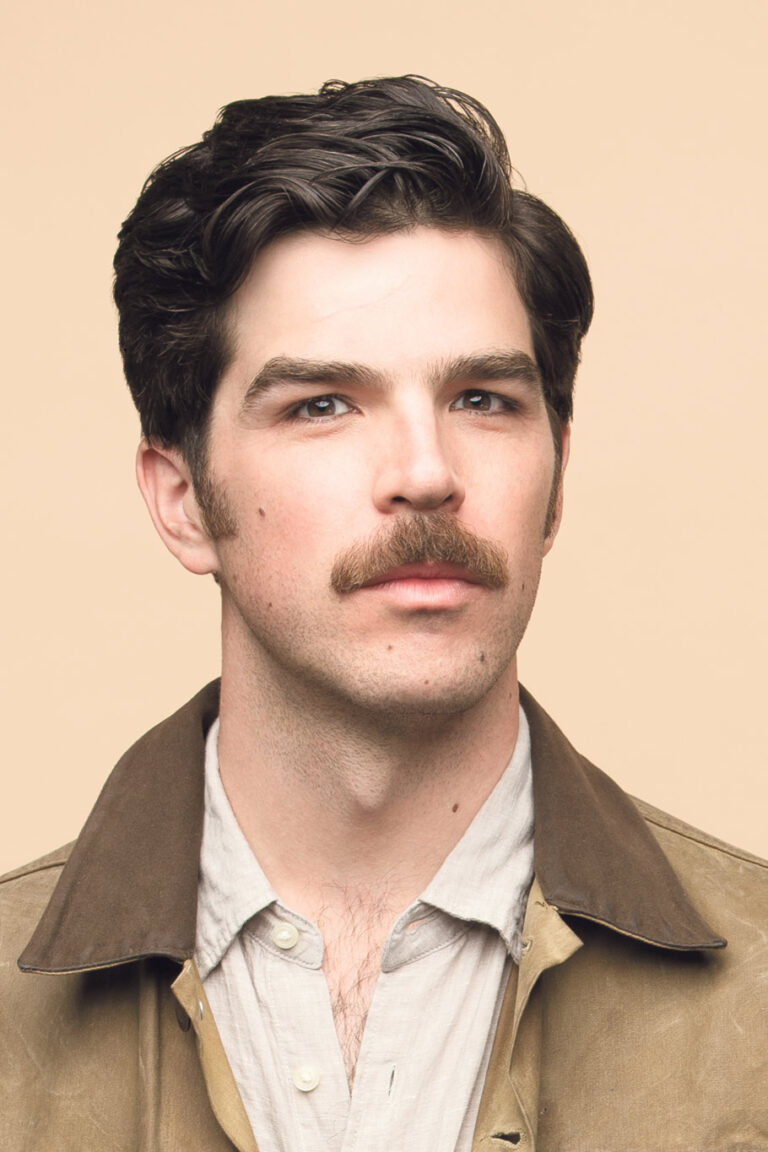

Author Francisco Cantú Discusses His Work On The Border

Author Francisco Cantú explores his experiences as a Border Patrol Agent in his book, The Line Becomes a River

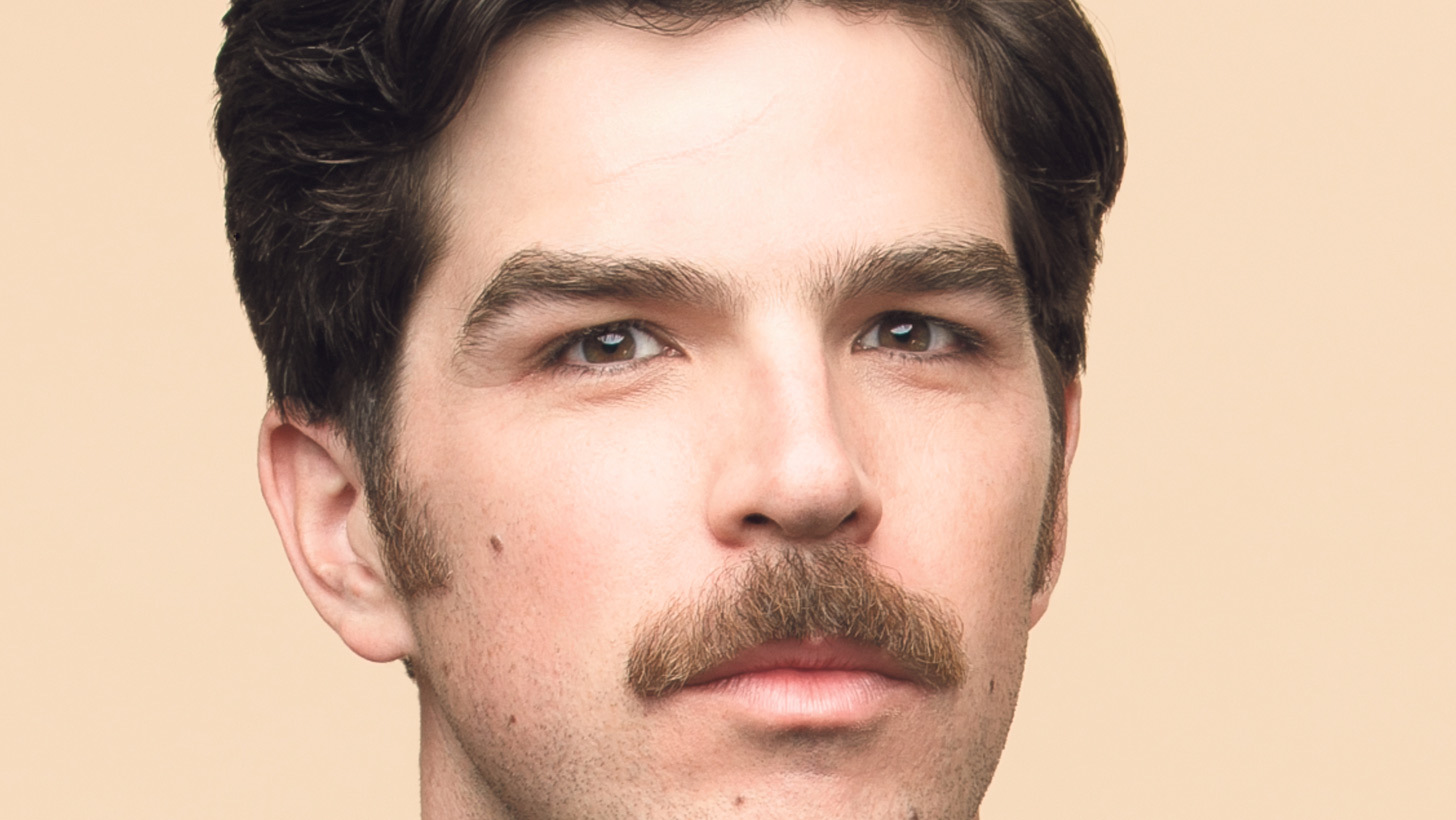

Beowulf Sheehan