Culture Shock: Translating Memory In Eight Languages

New Book Series Explores The Stories Of Refugee Children

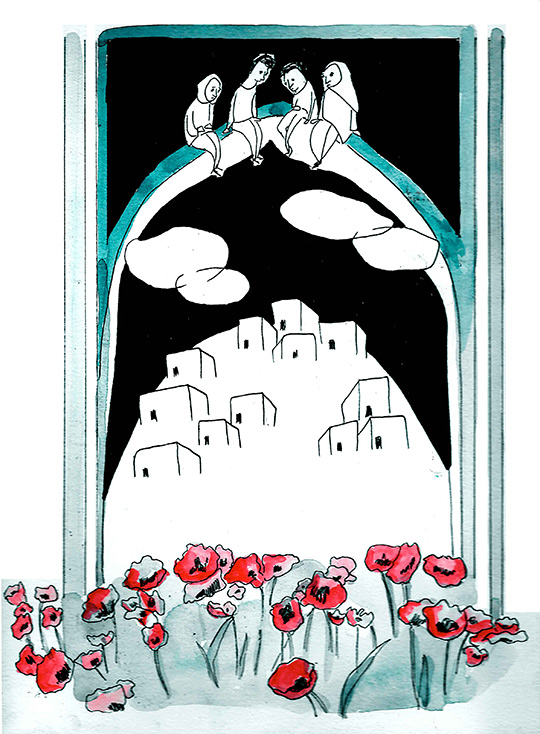

“Leaving Kabul”

Zahra Marwan

Artist Zahra Marwan unpacks her experiences as Kuwaiti and New Mexican

Zahra Marwan