Culture Shock: Visual Learning

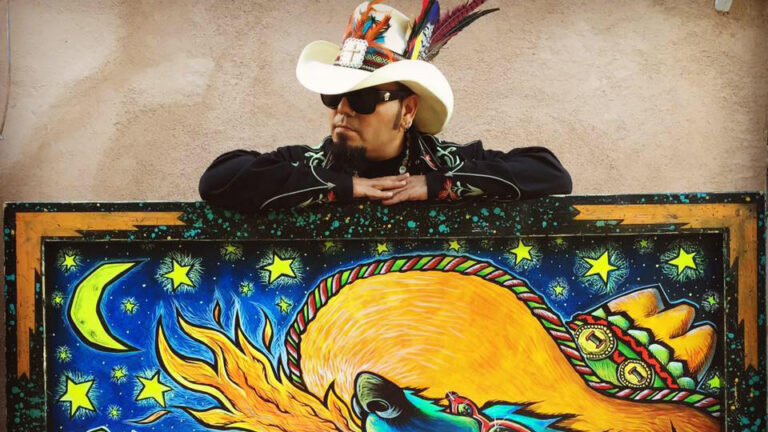

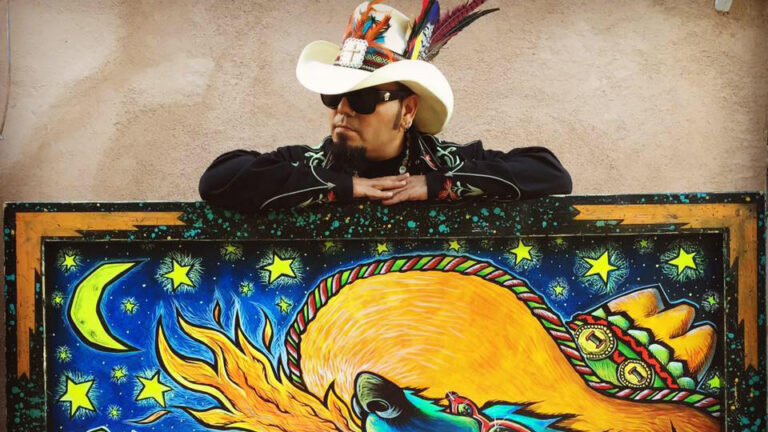

The “Badass Mother Folk Art” Of El Moisés

El Moisés

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

El Moisés