Culture Shock:a Line Carved Through Time

Exhibition And Book Illuminate Block Printmaking In New Mexico

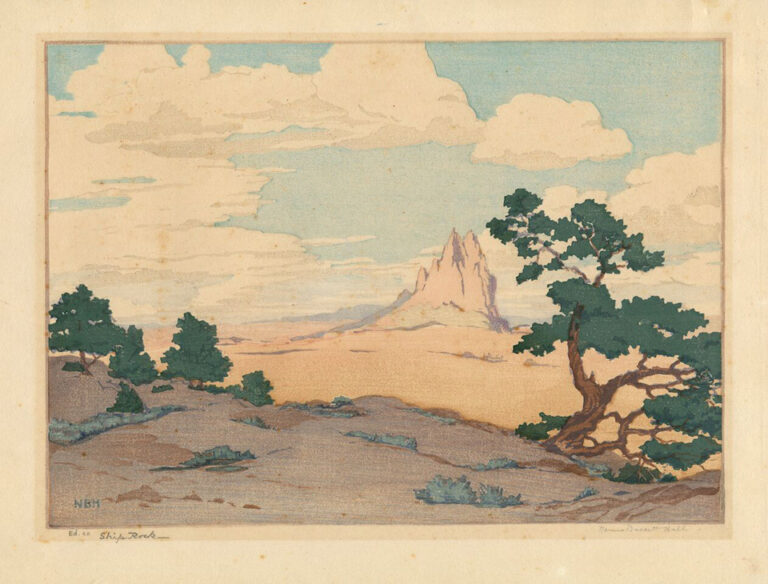

"Shiprock, New Mexico, 1940" by Norma Bassett Hall

Museum of New Mexico Press

"Cordova, 2006" by Thayer Carter

Museum of New Mexico Press