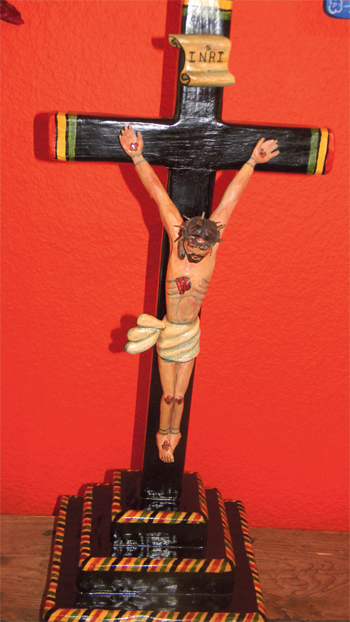

Artists sometimes talk about their craft as being therapeutic and meditative. But what about prayer-inspiring? Adán Carriaga, a 54-year-old santero (saint-maker) from the Old Town area says it’s not uncommon for santeros and santeras to worship while creating their iconic pieces.Saint-making is a devotional practice that tells the story of Catholic saints through retablos , panel paintings of saints, and bultos , hand-carved statues of saints.Carriaga is part of a talk on the subject at El Chante: Casa de Cultura on Saturday, Feb. 4. Artwork from 14 New Mexican saint-makers is also on display at the gallery and boutique in a show titled The Art of Devotion: Traditional and Contemporary. Charles Carrillo, a panelist at the talk, is a santero guru, author and archaeologist from Albuquerque who’s been making santos since 1978. Carrillo is at the forefront of his craft and has received numerous awards, including the Museum of International Folk Art’s Hispanic Heritage Award and the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Spanish Market, both in Santa Fe. He says religion is indivisible from the art form. “It’s an insult to the tradition if you are not Catholic,” Carrillo says. “You not only make it, but you believe in it.”Carriaga operates out of his Old Town spot, Carriaga Studio, which has a chapel. He refers to his work as folk art, and has been a practicing santero for 12 years. He’s an authority on the materials involved in the process. These include jelutong wood from Malaysia, noted for its lightweight and porous texture. Originally, cottonwood and cottonwood root were used. Carrillo says a cartographer named Bernardo Miera y Pacheco began the tradition in New Mexico during the Spanish Colonial period in the 1750s. Saint-makers also create their own watercolor-based paint out of mineral and clay pigments, plants and insect dyes. They even make their own gesso, a concoction of rabbit hide, glue, marble dust and plaster, Carriaga says. Gesso is applied before the paint to help the colors retain their vibrancy.A homemade varnish made from the sap of piñon trees and grain alcohol, called trementina , is applied to the artwork to seal and waterproof it. Finally, a beeswax coating dulls the glossiness.Carriaga, who helped coordinate the lineup for the event, says he’s hoping to keep the tradition going in the Albuquerque metro area. “I think it’s important as santeros and santeras that we continue the art,” he says. “It’s our responsibility to share and keep the art alive and preserve the history.” His daughters Monica Carriaga and Jenina Carriaga Lambert are saint-makers, along with his grandson Salvador Carriaga Lambert. The family dynamic is present in the show, beginning with the elder Carriaga’s take on “Our Lady of Sorrows.” Jenina’s and Salvador’s versions of the same saint surround his piece.Charles Carrillo’s work is more contemporary. His saints in cars and trucks, or “saints on wheels,” can have a humorous, cartoon-like quality. A retablo on display at El Chante called “St. Anthony” features the patron saint of lost things in a pickup truck.Since there are rarely formal classes on saint-making, “You can only hope that your family and your children take on the tradition,” Carrillo says, holding his 18-month-old granddaughter. In another year, he says he’ll start introducing the craft to her.

The Art of Devotion: Traditional and Contemporary

Talk on Saturday, Feb. 4, 4 p.m.Runs through Feb. 12 El Chante: Casa de Cultura 804 Park SW