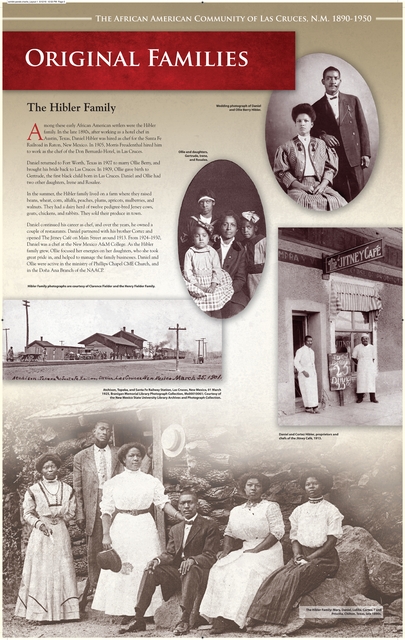

As a history nerd, I’ve often wondered what exactly it is that draws me to certain people or times. For example, I love me some medieval India, especially the Mughal Empire. Maybe it’s some past life thing, who knows? But it came up again for me while wandering around the National Hispanic Cultural Center exhibition New Mexico’s African American Legacy: Visible, Vital, Valuable. I was reminded of this freelance job I had a few years ago in which I wrote short biographies of notable African-Americans, anyone from John James Audubon to Charity Adams Earley, people about whom I knew nearly nothing when I started but who inspired me through their courageous actions. In the small exhibition, which is tucked into the library building at NHCC, two members of the same household highlighted as African-American founding families in New Mexico caught my eye. The first was Owen Smaulding, an Albuquerque High School student who, in 1915, was named the most outstanding athlete in the United States. Now, I’m not very sporty—I wear dress shoes and skirts when I ride my bike—so there’s no shared passion for athletics that would draw me to the baseball, basketball, football and track star.His brother, Chester, however, is totally my kind of guy. Chester and his wife Corine (aka Pert) owned Chet and Pert’s Flamingo Lounge, the first African-American-owned establishment in the state with a liquor license. Apparently the New Mexico Office of the State Historian is more of an Owen fan, because there isn’t a drop of info about Chester or his bar on its website or anywhere else on the web, though Owen has a very small write-up. Legacy is filled with information about the Smauldings and tons of other New Mexico African-American families I knew nothing about. And that’s its magic—this is one of those exhibits that teaches you things you didn’t know you wanted to know.When I first wandered into the building, I headed straight for some cases filled with stuff—and I found myself disappointed. There was a display with some textiles—a couple of hats, a pair of gloves and a collage by the Myrtle Church Sister Circle and Garden Club—but no information about why they were there or what they meant to the community. Another display featured paperwork about Mable Orndorff, a teacher who came to New Mexico in the ’50s to work at San Felipe Pueblo for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and who later received her master’s in education from UNM. The documents are interesting as artifacts, but without more context about why Orndorff is featured, the presentation falls somewhat flat. The compelling part of Legacy is the part many people ignore: the words. Yes, those giant placards on the wall, the ones normally full of information we all overlook—they’re really awesome. I want to sneak into the NHCC late at night, take them off the wall, make photocopies and take them home with me. Or I just want them published in a book somewhere so I don’t have to test whether the Alibi is willing to offer up bail money for my inspired, artistic shenanigans (I’m guessing no). But seriously, the information here is the kind of thing you just can’t easily find with an Internet search. People such as Dr. James Dennis, who surely had a lasting impression on the community, are featured. Dennis’ contributions came in the form of editing a newspaper called Southwest Review , being one of the first licensed African-American medical doctors in the state and helping to form the New Mexico chapter of the NAACP. It’s fascinating stuff, and through the research I did, I know just how buried the history and impact of African-Americans who lived during the first half of the 20 th century can be. My work ended up as a collectible set of cards advertised in Ebony magazine, a product I’ve never actually seen. Please, don’t let that happen with the work of curators at NHCC. No matter what your heritage, you’ll be inspired by the early African-American settlers who, like you, made New Mexico their home.

New Mexico’s African American Legacy: Visible, Vital, Valuable

Runs through Sept. 18National Hispanic Cultural Center1701 Fourth Street SWnationalhispaniccenter.org