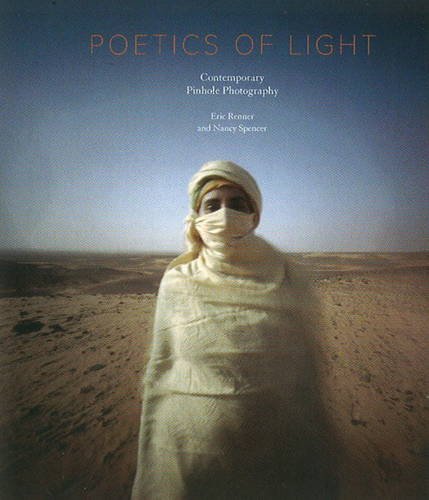

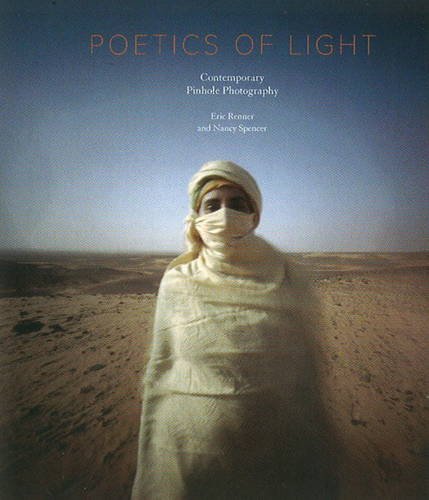

Get Lit: Light Looks Back In New Art Book On Pinhole Photography Tied To Santa Fe Exhibition

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992