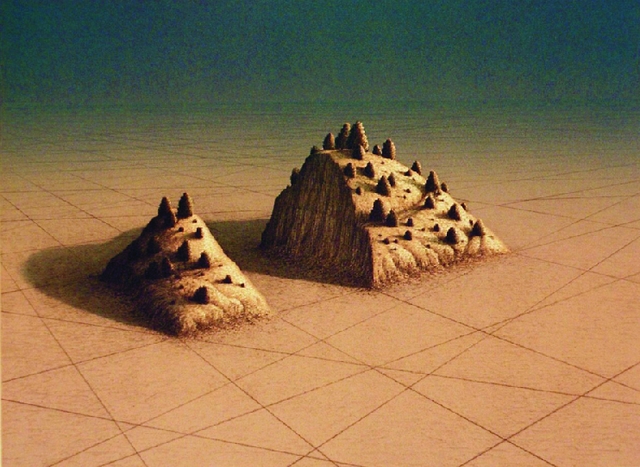

The fine art medium of lithography is a mysterious process to some and unknown to many more. Like daguerreotypes and woodcuts—two other kinds of image replication with far-reaching influence to modern expression—the lithograph has been relegated to niche status, the stuff of dusty museum archives. Yet many artists still prefer this rigorous, technical process. Bruce Lowney is one of them, having used the lithograph press to create beautiful, compelling works for more than 30 years.Opening this weekend at Artspace 116 in Downtown, The Imaginative Mind of Bruce Lowney will present a selection of many works that reflect the human condition and convey universal dilemmas through a mode of composition that far pre-dates photocopiers, scanners and Adobe Photoshop.“Drawings have always been my avenue of self-expression,” says Lowney, lining up piece after piece and propping them against the gallery walls in preparation for the exhibition. After receiving his MA in Printmaking from San Francisco State University, Lowney became a senior printer at the Tamarind Institute in the mid-’60s. Upon receiving a Louis Comfort Tiffany Fellowship, Lowney was able to purchase his own press and shop.From that time onward, Lowney has worked at his stomping grounds between Grants and Zuni, N. M. “I was a commercial printer until a big stone fell and busted my big toe,” says Lowney. “So I took that as a sign to get out of printing for others.” Lowney is also a self-taught painter, and he has produced a great deal of work on canvas over the last 20 years. Though working with oils provides more freedom on a larger scale, lithography gives him a chance to show the expertise of his life’s work.“The lithograph provides a beautiful surface to draw on, which you can then augment with color separation.” To many onlookers, it may be surprising that Lowney’s works usually come to fruition from about three runs of ink: a warm tone, a shadow tone and one for the actual detail of the image. “It’s an interesting puzzle, dealing with opacity and transparency in the layering of colored ink.”Looking at Lowney’s Water Under the Bridge and the subtlety of color in the image, it is hard to believe that the work came about from so few steps. Lowney has spent years perfecting his technique. Water-repellent oils are applied instead of pencil lead for the actual illustration, and the ink is forced by the water into these “dark” areas. Colors and tones can change dramatically (and sometimes disastrously) with a slight change in the application and volume of ink.Traditionally, every print in an edition is numbered in the lower corner of the piece, and new editions are always specified to ensure a work’s authenticity. “This is the aesthetic of Tamarind, one that demands a curatorial attention to detail: Every print has to match.” Lowney, however, would rather the viewer focus on the title than the little number next to it. In The Diver , the escape to freedom from the oppressive suburban world, represented by picket fences crushed by the rushing tide, becomes striking and unmistakable.Though some pieces in this exhibition have been reprinted in subsequent editions, it is a testament to the nature of lithography and the printmaker’s skill that they are indistinguishable from the originals. Despite this, it is not Lowney’s intention to draw more attention to only few works. “I don’t use the word ‘series,’ since that connotes a succession of images with similar content and themes,” Lowney says. “It’s a matter of looking at the entire exhibition, and the space in which the works are displayed, to create an exhibition from which people will take meaning.”

The Imaginative Mind of Bruce Lowney opens with a reception from 5 to 8 p.m. on Friday, Dec. 7, at Artspace 116 (116 Central SW, 245-4200) and will be on display through Feb. 8, 2008. For more info, visit www.artspace116.org.