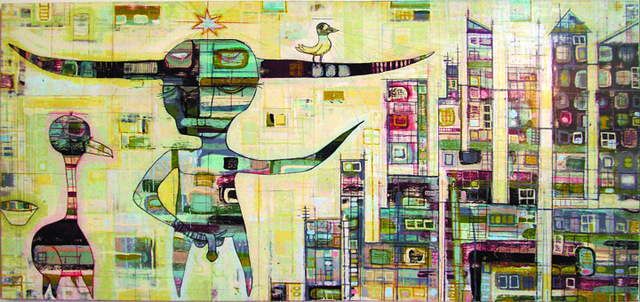

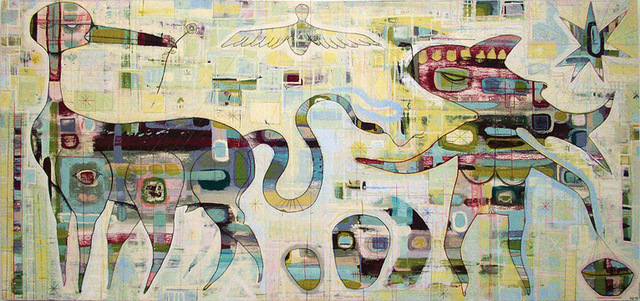

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur was a monster with the body of a man and the head of a bull. His birth story starts with Minos. Minos prayed to Poseidon, highly temperamental god of the sea, to send him a sign that the throne of Crete would be his. Poseidon sent a snow-white bull intended for sacrifice, but instead, Minos decided to keep it for its beauty and sacrifice another. Naturally, Poseidon was peeved, and in spectacularly weird Greek myth fashion, made Minos’ wife Pasiphaë fall in love with the bull. She in turn asked the famed architect Daedalus to build her a wooden cow that she climbed inside of in order to mate with the bull. The progeny of this cursed coupling was the Minotaur, who was later imprisoned in a labyrinth and killed by the hero Theseus for various assorted, well, labyrinthian reasons. Though Greek mythology was a favorite topic of artists for thousands of years, the 20 th century saw a decline in the influence of Western culture’s oldest and best-known stories. Instead, modern art has typically been focused on the current, the all-consuming attraction of what’s in front of us now. It’s striking, then, to walk into one of the city’s newest and most modern galleries and see an entire room filled with portrayals of creatures from ancient myths. Thomas Christopher Haag’s show in the main gallery at Cirq Art Gallery and Boutique is as thoroughly modern as Millie. Yet it employs a cast culled from the belief systems of earlier civilizations in order to explore how we came to be here and who we are.The pieces in Haag’s show range from a series of eight 11-by-11 acrylic and pencil on board pieces, collectively titled "Greater Arcana," to larger paintings rendered on hollow-core doors. The Minotaur appears in much of the work, along with various fantastic creatures—hybrids of bird, snake and cow, armless cats, a devil. The effect, though, is never grotesque, nor are these the smooth and muscled characters of Renaissance sculptors. Instead, Haag’s subjects are disproportioned, kinetic. There’s a fanciful quality to them, though they stay away from twee with the insertion of sharp lines and blank spaces functioning as palimpsests, thin enough to see portions of what’s been painted over. Haag’s paintings use a decidedly modern palette—desaturated, the color of walls in the houses of Dwell . It’s a smart choice, since it allows the work moments of density without seeming busy. Lines permeate each piece, as if placing the figures on a graph, creating a scale that’s often surprising and absurd. It’s the use of these contemporary devices in the portrayal of ancient myths that creates question identity. Are we so modern that our origins stretch only as far back as cluttered cities, such as the ones suggested in Haag’s larger pieces? Or do we, like the Greeks, still yearn to know from whence we came? And if so, what is our narrative? Who is our foolish King Minos, what is our Minotaur?In one of my favorite pieces, "Minotaur Leaves the Labyrinth," we get an image from a scene that didn’t happen in the original. Instead of getting killed for being unnatural, monstrous, the Minotaur breaks free from the maze, clustered like a city behind him. He is in the midst of openness, his penis flaccid, a bright star above him. In Haag’s work, mythology is employed as part of our collective vocabulary; but instead of offering definitive pronouncements, its use becomes a way to write a new story. No less weird, but infinitely more immediate.

Cirq Art Gallery and Boutique is located at 712 Central SE. For hours and more, call 242-3970 or go to cirqgallery.com.