Poetry News: Artist In Residence At Nhcc Explains Projects, Joins Regional Slam Competition

Nhcc’s Resident Word-Slinger Will Join Southwest Shootout

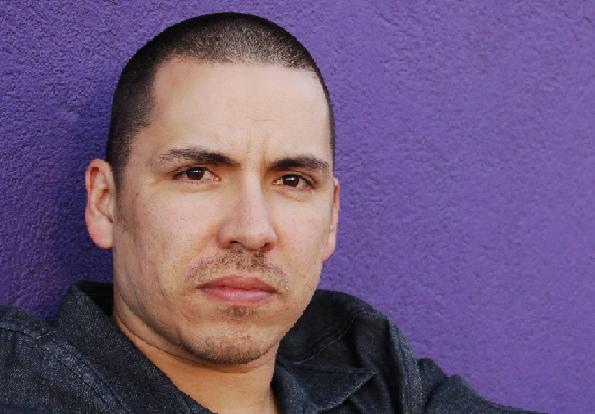

Joaquin Zihuatanejo

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Joaquin Zihuatanejo