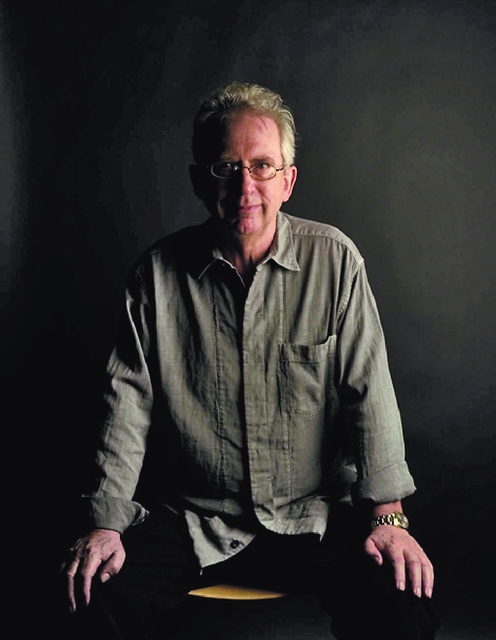

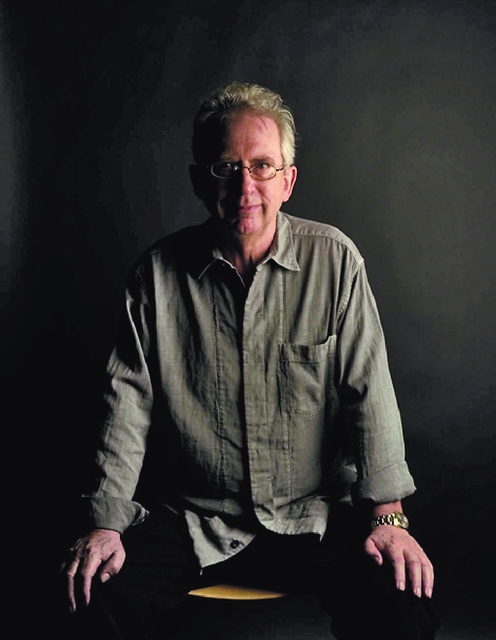

The word “happy” does not fit easily into Peter Carey’s mouth. Under normal circumstances, it dribbles off his lip on a trickle of sarcasm.But not long ago the two-time Booker Prize-winning novelist began using the word about himself without apology, and more than ever.“I was miserable for a long time,” says Carey, 64, sitting in his large, airy lower Manhattan loft. “I just thought—the kids will grow up, and I’ll die. Then I turned 60 and I was suddenly amazingly happy.”Behind him are two striking paintings—one enormous, the other small—both by painters who’d lived in Australia. The small one, picturing the Santa Monica freeway, is titled Study # 3 for “Crossroads” by Jim Doolin, the other is Three Crossings by David Rankin.The choice of decoration couldn’t be more apt. As hard as it is to imagine, after two Bookers and numerous bestsellers, Carey is passing through another crossroads and has begun to feel the breeze on his back again.Toward the end of our interview, one of the biggest forces behind this shift walks in the door bearing chocolate torts the size of oven mitts. Frances Coady is the publisher of Picador USA and editor of such writers as Paul Auster, Alan Bennett, and the great historian and activist Naomi Klein.Carey and Caody have been together for nearly five years and sharing an apartment for two. Their paths crossed first in 1985, but they didn’t properly meet until after Carey’s divorce to Alison Summers was underway.“It took me two years to call her,” Carey remembers. “She was always so full of life and energy and with somebody. And then she wasn’t.”They’ve been together ever since, and make for an amusing pair—the diminutive, large-eyed, raspy-voiced Coady often goading and scolding Carey, who grumbles and skulks under his breath.It’s hard not to wonder how much this newfound domestic happiness has to do with Carey’s unbelievable burst of productivity. Since 2003, Carey has published four books. His latest, His Illegal Self , is a road novel that culminates on a hippy commune in Queensland.Along the way it tells the story of Che, a 7-year-old boy raised by his wealthy grandmother in New York. As the story begins, though, Che is smuggled out of the country and into a manic quest through the Outback to find his parents, famous outlaws wanted by the FBI.It’s Carey’s 10 th novel and the latest in a strong series of stories about a character divided between two places and not entirely belonging to either. “If I think about it, every single one of my novels deals with this idea of being in two places,” Carey says.There was a place he wanted to revisit—the land near Queensland where he lived quite contentedly (and eventfully) in the ’70s in a collaborative community after working in advertising. “No one asked me, What do you do? People had simple needs,” Carey remembers. “I used to write in the morning and read at night.”It was an ideal life, except when Carey lived there the police were crooked and dangerous, he says, and the hippies just as likely to be Maoists. Carey has written of this period before in Bliss (1981) and revisits it now in a less comic vein and from a child’s point of view. Satire, he felt, was not really an option. "A lot of radicals in this period came from quite privileged backgrounds. And they ended up going all the way. A lot of my Maoist friends used to say, After the revolution, you will be shot. They weren’t entirely kidding. But the people in this commune were ahead of their time; they were worried about carbon footprints, about whether or not we could sustain this way of life we have going now, which we now know is unsustainable.”In beginning His Illegal Self , Carey decided he would not simply bring this world back. “It cannot be the same place,” he says. “That place existed 30 years ago. A mirror or shadow of it remains in my head. Working with this afterimage, I fashioned a new place whose topography and inhabitants exist only to serve my story.”As he has aged, Carey has become less interested in satire and more interested in sentences. “Since The Kelly Gang , I aspired to make a poetry out of an unlettered voice,” Carey says, “and ever since I’ve been obsessed with bending, snapping and reshaping sentences, trying to join things in ways that are not at first apparent.”Coady, not surprisingly, has become his first audience of late, often at the end of the day when Carey will read her what he has written that morning over a glass of wine. Carey says she hasn’t changed what he writes, but is a superb reader.“She can echo things back to me that are tremendous. And she’ll tell me when things aren’t working.”This workshop isn’t the only one Carey has been conducting. For the past four years, Carey has been director and now executive director of Hunter College’s Masters of Fine Arts writing program—perhaps the cheapest (and now one of the best) way to get a writing degree in Manhattan. "This is the first time I’ve taken something like this on,” Carey says. “I took it on because I could make something and I didn’t see why the university couldn’t be the best MFA program in the city.”Just as Illywacker preceded his Booker Prize winner, Oscar & Lucinda , and Jack Maggs his second Booker winner, The True History of the Kelly Gang , it seems like His Illegal Self might be the beginnings of a new stage in Carey’s career, marked by momentum and tidier, snappier sentences.I ask Carey if this palpable sense of creation has to do with happiness and he shrugs it off. “I was working on The Tax Inspector when I was relatively keen and yet the sense of this dark book almost seemed to invade my life. It’s hard to know what qualities of your life enter your work,” he says in the end. Whatever they are, Carey isn’t going to think too hard on them, nor will he ever, in his right mind, allow himself to jinx it.

John Freeman is president of the National Book Critics Circle.