Estampas de la Raza

Closing reception with a talk by Gustavo Arellano, music by The Big Spank and printmaking demosThursday, Sept. 19, 5 to 8:30pmFreeAlbuquerque Museum2000 Mountain NW842-0111, albuquerquemuseum.orgThe Mexican Abides: “¡Ask A Mexican!” Columnist On Art And La Raza

“¡Ask A Mexican!” Columnist On Art And La Raza

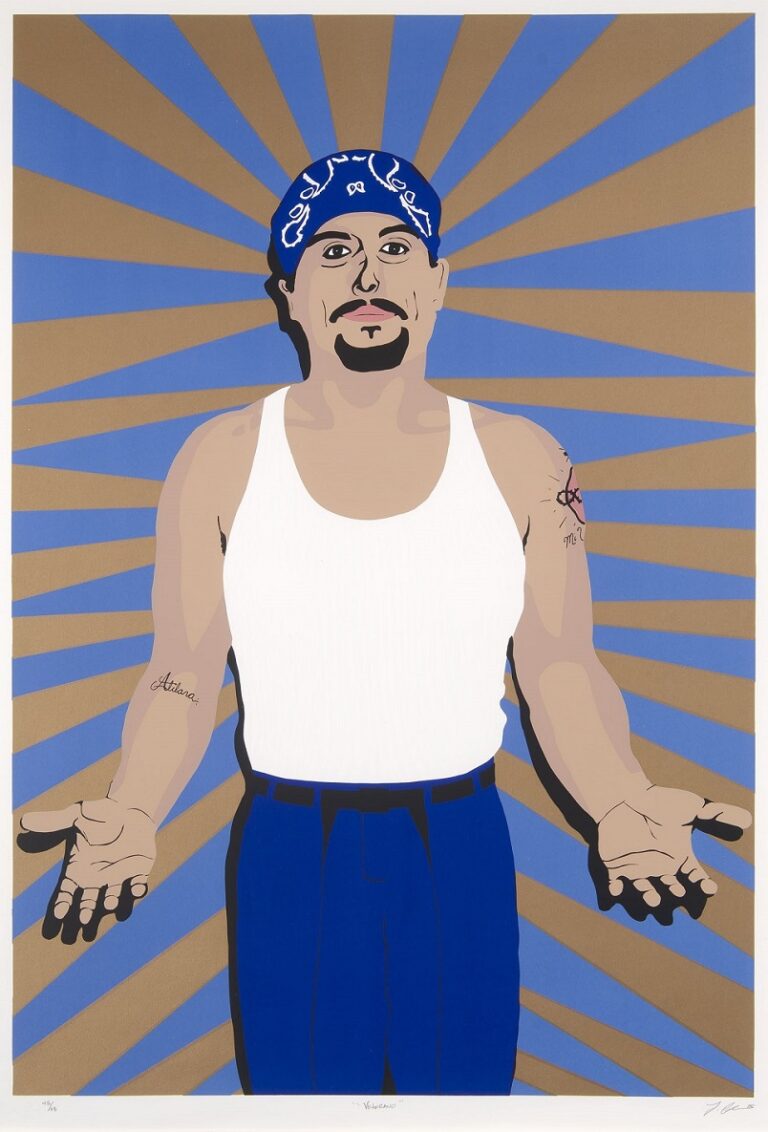

Lawrence Colación, “Veterano,” 1995, serigraph on paper

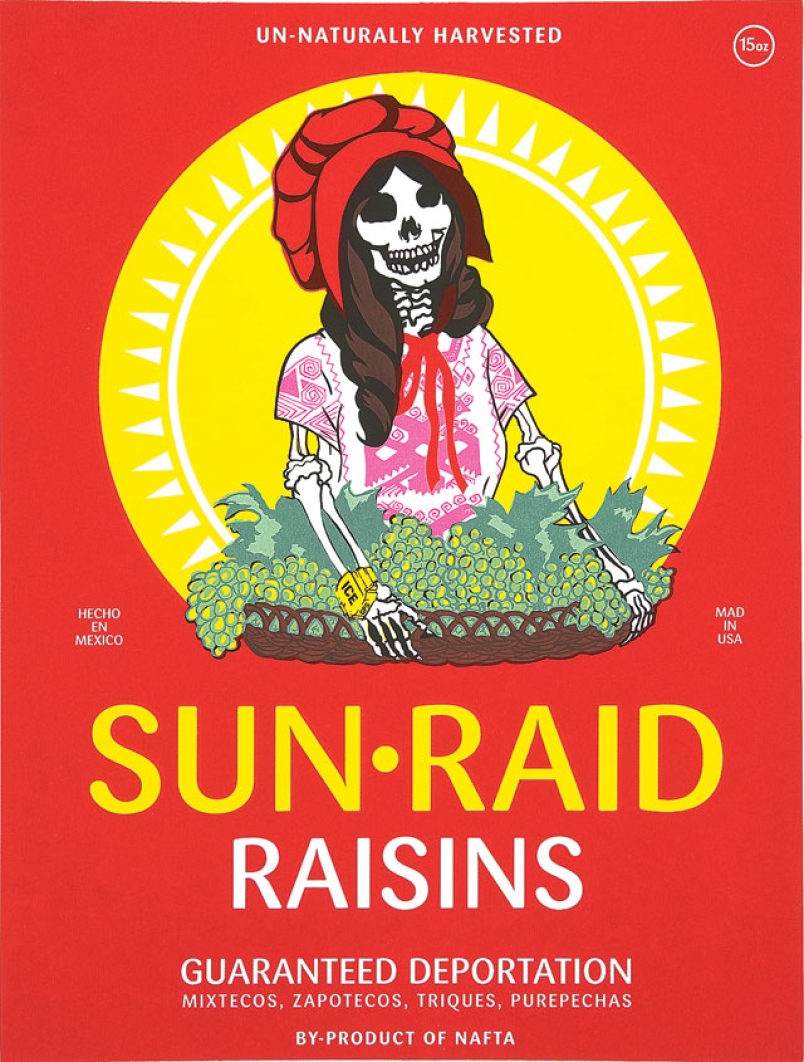

Artemio Rodriguez, “Mickey Muerto,” 2005, screenprint