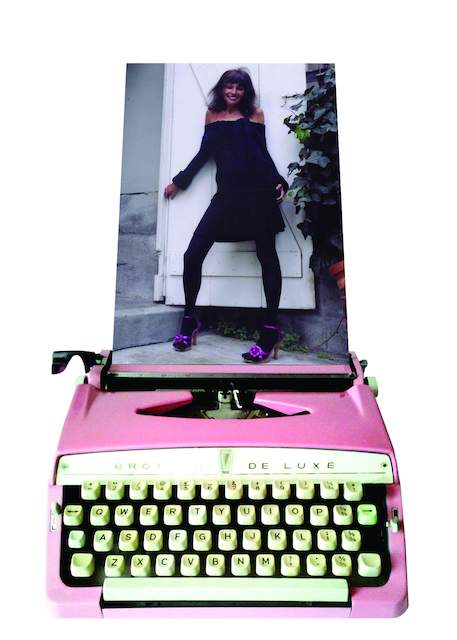

Kate Braverman is dressed in all black—heels, leggings, dress, fur coat, hat—all dark and mysterious. It makes sense. Braverman is the kind of writer who layers her emotions—the cheerless, dreary thoughts most people are uncomfortable with—into everything she writes. She published her first novel Lithium for Medea in 1979, the semi-autobiographical story of a drug addict struggling with an emotionally withdrawn mother, an abusive boyfriend and the impending death of her father. Her writing is uncompromising, unafraid. Her personality is no different. When she sits down, we jump right in on some Sylvia Plath.“She’s a compendium of modernism,” Braverman says. “We say that literature post-WWII is about the unreliable narrator, and she ups it one step. No longer is she just unreliable, she’s a ‘pathological liar’—the boldness of that stance, how it takes everything in English and upends it.”She quotes Plath effortlessly, waving her arms to the cadences of the words, her hands flowing to the rhythm of Plath’s bold, groundbreaking stanzas. A writer for over three decades and author of fearsome works like Palm Latitudes and The Incantation of Frida K., Braverman’s dissatisfaction with the modern landscape of the written word proves palpable. And it’s this literary ennui that has prompted her to start a writing residency to reinstate interest in the American tome.“You used to go to a dinner party, a gathering, and it would be de rigueur to talk about John Updike, the new Philip Roth. Now no one talks about books, at least where I go, unless maybe in a secret enclave of book talkers,” says Braverman. “And I don’t think readers get enough credit. Reading is a skill, and increasingly a skill in this culture, when everything keeps you from reading. You won’t be able to talk about it or have a conversation [about] the controversy, which is why I’ve started this series of literary conversations. Books should be talked about, should be debated. It’s not something you should do in silence.”Braverman stresses that it’s not just the practice of reading that has changed in America, but also the way books are written.“I want to pass on the schematics of old-style writing because they’re going to disappear. No one will ever write again the way I write. And no one reads anymore like Sylvia Plath. She was on a reading fellowship. You know they used to have that?” she asks, her intent eyes staring into me. I tell her I didn’t.“You can immediately become a better writer by not writing anything for a year and just reading. Do you wanna become twice the writer you are today? Don’t write a word, and read for the next 12 months. You will be astounded.”Now in her sixties, Braverman reminds me of a displeased grandmother, the kind of person who tells you how great things used to be. It’s an old story, but Braverman expresses it with viable earnestness. As she orders a cocktail, I ask her why she thinks the world of writing and publishing is in such disarray.“I think that there’s no more of a critical apparatus,” she says, taking a sip of her drink. “There used to be a real system for reviewing. When I went on a book tour for my last book, there were 13 book review sections left in America. There are now two. The Chicago Tribune is gone. The Philadelphia Inquirer used to do good reviews. But the chances for review are no longer legitimate. The entire system has collapsed.”She stops to acknowledge her dire point of view and apologizes for sounding so depressing. No more adequate venues for good writers? I ask Braverman if she doesn’t think she’s going a little far. But she claims the act of writing itself is in danger.“When I’m gone and people like me are gone, there will be no way to know how books were written before the computer,” she says. “When you do a spell-check on the computer, you get four choices of words. They’re similar. When you go to a dictionary, you get 400 choices. And if you read through those choices, you look for similarities to those 400 and end up with completely new word choices.“The speed of writing now is unnatural. The way you can move a paragraph, this pause is gone. You had to be more careful with rewriting because of the physical labor, which people [nowadays] have no knowledge about.”We return to the critical portrait she paints of today’s writers. While Braverman alludes to the fact that writing used to be done by the aristocracy, for the aristocracy, and how only educated people were considered good authors, I ask if she believes there are modern storytellers who possess natural talent.“There are many people who are naturally good, [but] I think you do need to study, and you have to be very careful with the studying because that’s part of the standardization the American consciousness is going through,” she says. “The idea that now everyone has an MFA, it’s a kind of standardization. If you think of the writers in the early 20th century, no one had an MFA. They were journalists; they were war correspondents. They weren’t teaching; they weren’t part of academia. They worked at advertising agencies. They had jobs. That’s a major change.“I am uncomfortable when people say they are poets or writers when they have not published on a national level. Yes, just like if someone walked around with a toy stethoscope and said, I’m a doctor. You’re not a doctor. You’re pretending. Somehow, we’ve lost the difference between an aspiration and a reality.”Braverman hopes that with the Santa Fe Writing Residency, which starts on Feb. 10, she’ll be able to instill a more old-school approach to how people go about their craft. “That’s why I call my workshop a residency,” Braverman says. “I’m a specialist, like a doctor. You spend a certain amount of hours and other preparations, and then you go for a specialty. I have a specialty. There are certain things I do incredibly well. ‘Dying is an art. I do it [so] it feels real.’ I guess you can say I have a calling.”

Santa Fe Writing Residencywith Kate BravermanMaria’s New Mexican Kitchen555 W. Cordova Rd., Santa FeEvery Tuesday, beginning Feb. 10, from 1pm to 4pm (continues indefinitely)$125 for four weeksEmail keb60@live.com to reserve a spot.katebraverman.com