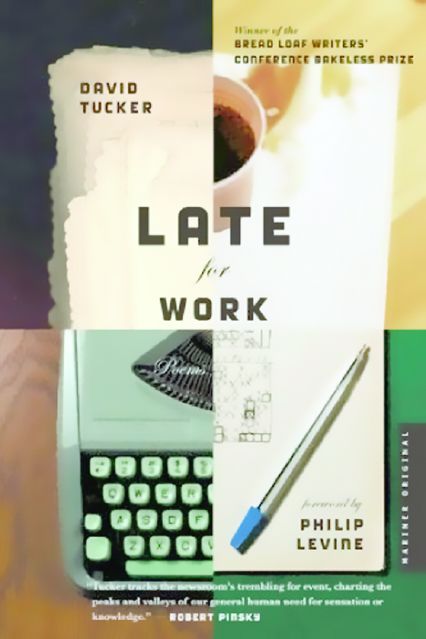

Late For Work

Hell In A Handbasket: Dispatches From The Country Formerly Known As America

High Lonesome (Stories: 1966-2006)

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992