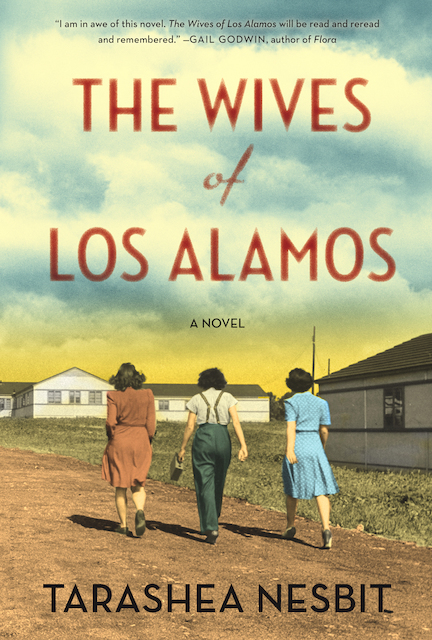

Windblown. Mercurial. Potrero—“dry tongue of land.” Buzz of enterprise. Los Alamos, the birthplace of the atomic bomb, comes alive in TaraShea Nesbit’s debut novel The Wives of Los Alamos. The fictional story depicts a Los Alamos that hums with secrets, slights and insights. Set in the early 1940s, the book is told from the perspective of the wives of nuclear scientists newly arrived in the northern New Mexico town. Nesbit draws from firsthand accounts and other research to tell the tale of these women and their involvement (or lack thereof) in Los Alamos social and laboratory life. The voices of men are absent, the purpose for arriving “out west” hazy, and the reader’s awareness transforms alongside the women who attempted the routine in precarious conditions. “A friend told me about a former secret Manhattan Project site—the high school [where they] were the ‘Atomic Bombers’ and their mascot was a mushroom cloud; crazy stuff,” the author told me during a recent interview. More than the dark humor inherent in the mascot, the town made Nesbit curious about the “loyalty and culpability” of its inhabitants during the Atomic Age. She began researching other Manhattan Project sites and the people involved. Over the years-long period Nesbit spent researching atomic legacy, life continued: She married, moved to Denver and joined new communities of friends and colleagues. Her daily life began to push on the stories she uncovered from the past, and she wondered, “What created the bomb? What about these normal people—husbands and wives?” Reading Nesbit’s novel is a bit like discovering an intelligent, lyrical diary by your mother or grandmother. The details feel both familiar and foreign. The wives remove their torn hosiery and scuffed-up heels in exchange for the sturdy blue jeans that become their “new power.” The wives travel to Santa Fe with a mission to throw off the locals—they are told to drink and dance and whisper about the electronic rocket ship being built in the hills. The wives soothe their children and try to reach their husbands over commissary-furnished dinner at night. Nesbit hauntingly captures these voices with first person plural as a collective we: “We arrived at 7,200 feet above sea level dizzy, sweaty, and nauseous … we arrived in need of a shampoo … as if we were not resentful that we did not have a choice.” Listening to the oral histories of women who lived in the atomic village, Nesbit was struck by the way that they spoke in the communal "we" instead of as individuals. “It totally made sense to me,” said Nesbit. “The way they identified was primarily a group identity.” In capturing the voice of the wives, Nesbit has created a rhythmic chorus. Throughout, the men surface in flashes of laughter, brooding and appetite. Nesbit hoped that readers would walk away with just this sense of blinkered vision. In her research on the war and Los Alamos, Nesbit “found out all this information.” She had to remember, though, “these women didn’t know; I was trying to stick with what they actually knew.” The women’s sense of New Mexico was profoundly shaped by the pueblo men and women who worked in the (overwhelmingly white) Los Alamos community. The scientists’ wives could be “a little bit othering,” Nesbit noted. She learned the husbands would sometimes perform impersonations at parties, dressing up in shawls and jewelry. “I think it’s a really important part of the book,” the author said of the relationship between the local workers and wives. Her exhaustive research makes for vivid scenes in the book against a background of cocktail parties and Oppenheimer ogling. “I wanted to give all the pieces of this town, this life, and let the reader experience it as they would,” Nesbit said. And, of course, rumbling behind the whiskey drinks, the flirtations with the stationed soldiers, the constantly thirsty skin, is the war. From hometown letters, The Santa Fe New Mexican and the arrivals of new families, the wives learn of the casualties and victories abroad. They are aware that they are an intrinsic part of it, somehow. “We thought—we hoped—our husbands were working on code-breaking,” the wives voice in unison, “but our husbands were physicists and we had to consider what they might be able to build using their skills. We considered a weapon. We sometimes hoped our husbands would fail.” Nesbit has chosen to write a war story in which the heroes shift and become ciphers. The protectors are the wives’ brothers fighting abroad; they are the Tewa women who bake them prune pies, the husbands who marvel and wonder at their crushing creation. Above all, they are the women who have made Los Alamos their own. Nesbit said, “The war story is often a heroic story, and it’s important to give voice to the voiceless.” With The Wives of Los Alamos, she delivers new expression in a staggering chapter of our nation’s history.

TaraShea Nesbit reads from The Wives of Los Alamos

Sunday, March 9, 3pmBookworks4022 Rio Grande NW344-8139, bkwrks.com