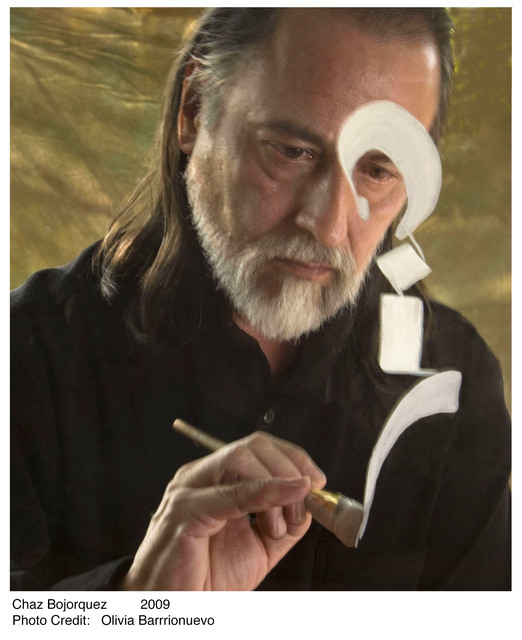

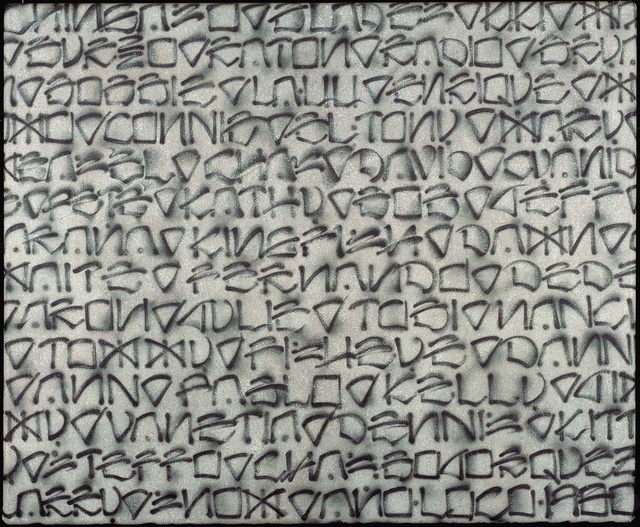

Chaz Bojórquez has never been caught, but he has been chased. He laughs when he admits it, because it seems slightly absurd: a world-renowned artist with work hanging permanently in the Smithsonian American Art Museum being pursued by cops for painting something on the side of a building. Such is the life of a graffiti artist. Even if you don’t recognize his name, you’d probably recognize Bojórquez’ work. He’s most well-known for a skull he designed that’s referred to as Señor Suerte, which he stenciled all over Los Angeles in the ’70s and became a symbol of protection among street gangs. Bojórquez’ cholo-style-graffiti-meets-Asian-calligraphy has inspired generations of street artists and shown in galleries across the globe. It’s hard to imagine he got his start tagging a garage door.Bojórquez was 19 (he’s 61 now). He says he was so poor, he lived off 14-cent cans of mackerel he’d somehow always end up splitting with a cat. He couldn’t afford a spray can, so his first tag was administered with a squeegee and ink he found. He wrote his name. “All graffiti kids write their name,” he says. “This me-me-me mentality.” But his world view gradually shifted. A few years later, he wrote about himself and his girlfriend, then it was his neighborhood, then the world. That final shift was due in part to the year and a half Bojórquez spent visiting and living in 35 countries, where he learned about how the physical representations of alphabets influence cultures, along with the three months he spent studying calligraphy under Master Yun Chung Chiang (who in turn studied under Pu Ju, who was brothers with the last emperor of China). In an age when graffiti-as-art is still censored, Bojórquez serves as a perfect spokesperson, although he doesn’t perch himself on his soapbox very often. “If I spent all my time defending graffiti,” he says, “then I’d have no time to going forward with graffiti.”He says people often ask him whether he’s setting a good example for youth, and his response is always that the best thing he can do is finish his work. He tells kids: “Do more graffiti.” By practicing more, he argues, kids will improve their skills and evolve out of the illegal graffiti world and into the artistic one. “They’ll buy graffiti magazines, watch videos, go to galleries to meet the players,” he says. “People like me, there are only about three dozen of us over the world; we’re like superstars. Once kids want to be like that, they’re too busy making prints and paintings to do illegal stuff.” He says his job is to show them what they can become, to prove that “making a life with art is a beautiful thing.”Most of Bojórquez’ work now takes place off the streets, although he says he’ll never stop tagging (hence the chasing). Within the last few years, he’s started designing products, such as some Vans shoes, menswear for Conart Clothing and wine labels for the Plata Wine Company. “I want to be in culture,” he says.It’s easy to see that culture and its effects on identity and personal freedom fascinates Bojórquez, who says graffiti is, like any other artistic method, ultimately about expression. “It’s a need for self-expression, for self-identity, for personal growth,” he says. “Because it’s been a part of our culture since caveman times. It’s part of the human need to be identified, to leave your mark. We’re hardwired for it.”Bojórquez says people should be able to leave their mark in some way—that if billboards promoting cigarettes and alcohol are legal just because they’re paid for, people should be allowed to leave a sign that they’d been somewhere, that they belong there.“Who really owns the public space?” he asks. “In some ways, graffiti doesn’t ask permission. We don’t ask for permission; we don’t ask for forgiveness. It’s a passion.”

Chaz Bojórquez

Work showing through Dec. 11 at

516 ARTS516 Central SW

Public Conversation: Sunday, Oct. 3, 1 p.m.

Albuquerque Museum2000 Mountain NW