A Tribe Apart And Alone: Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend Exposes Hard Choices For Native Youth

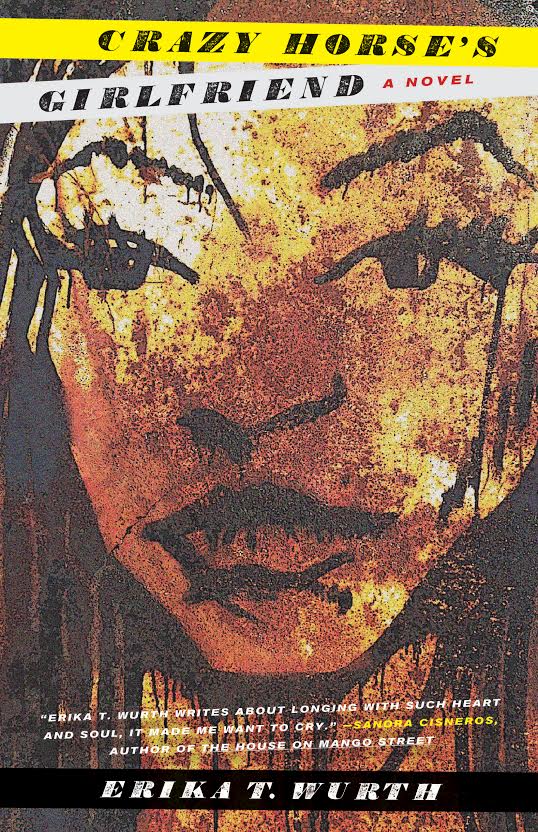

Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend Exposes Hard Choices For Native Youth

Erika T. Wurth