Ghost Ranch has been so named only since 1928, shortly before Carol Bishop Stanley moved there after divorcing her first husband, who’d won the acreage, the story goes, in a poker game. The so-called ghosts are likely those of the outlaw Archuleta brothers, who late in the 19th century ran a cattle-rustling operation under the shadows of the red cliffs until one brother killed the other in an argument over buried gold and the rest of the outfit quickly, and wisely, dispersed. This riveting episode comprises the first of many stories vividly retold by Poling-Kempes.

Carol Stanley realized early on she’d need to have paying customers to keep the land, and her decision to open a guest ranch created an influx of wealthy Anglos who soon came to Ghost Ranch, some to visit and some, it would turn out, to stay. Among those who stayed was the millionaire conservationist Arthur Pack—who founded, among other enterprises, Nature magazine—and his family, who purchased the ranch from Stanley in 1935, when she could no longer afford to run it herself. Pack ran Ghost Ranch for the next 20 years, treading a cautious line between human enterprise and land preservation, and another between the people themselves, such as his first wife, who ran off with a young Pack protégé, and the already famous artist Georgia O’Keeffe.

This book, of course, includes the obligatory O’Keeffe chapter. While Arthur Pack (and, later, the Presbyterian Church) may have been the owner of Ghost Ranch, it’s O’Keeffe who rendered the Piedra Lumbre iconic. Yet other than some amusing anecdotes about her particular sense of entitlement, there’s little in this chapter that hasn’t been covered more extensively in other books. Still, a Ghost Ranch book without O’Keeffe wouldn’t be complete.

What’s more intriguing is the role Ghost Ranch played for the Los Alamos scientists during World War II. After successfully passing the muster of what the Packs called the “Junior G-men,” the ranch became a weekend retreat for the men and women who worked at the unnamed top-secret facility. While the Packs recognized some of the scientists “with all-American names like Nicholas Baker and Eugene Farmer, but with decidedly non-American accents,” discussing what was going on “up the hill” was forbidden, and it wasn’t until after the war that they let others know their frequent guests had included Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi and Niels Bohr.

In addition to such significant 20th century characters, Ghost Ranch’s storied past includes thousands of dinosaurs, unearthed by paleontologists after World War II. In 1955, Pack donated the ranch to the Presbyterian Church for use as an educational facility, shepherding in the era of the conference retreat that continues to this day. Poling-Kemper lovingly recalls Jim Hall, the preacher-director responsible for this remarkable transformation, and a man clearly important to her as well.

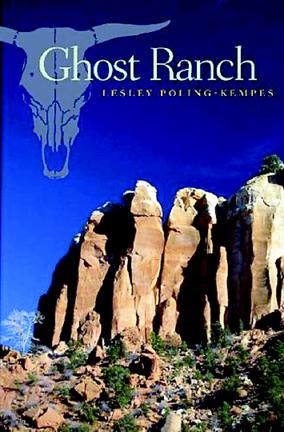

Whether it’s millionaires and movie stars, physicists and paleontologists, or painters and Presbyterians, Poling-Kempes is adept at drawing the characters who people Ghost Ranch’s past. Photos abound, some familiar, some less so. Unfortunately, the book doesn't include a map. But map or no, Ghost Ranch is one of those places that reminds us of our own transience by its very vernacular, and Poling-Kempes gives us both the place and the people who treasure it and keep it so—a fitting tribute to a holy place.