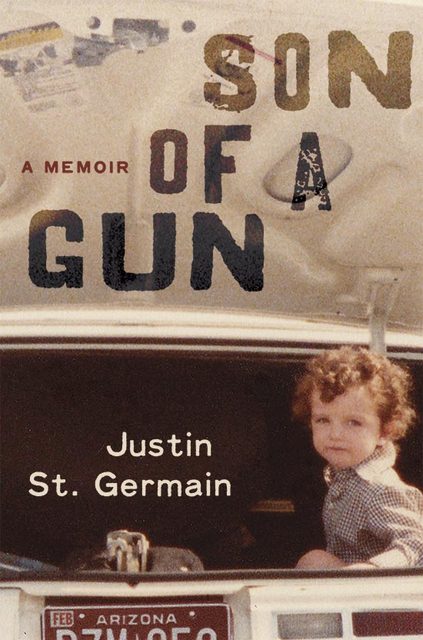

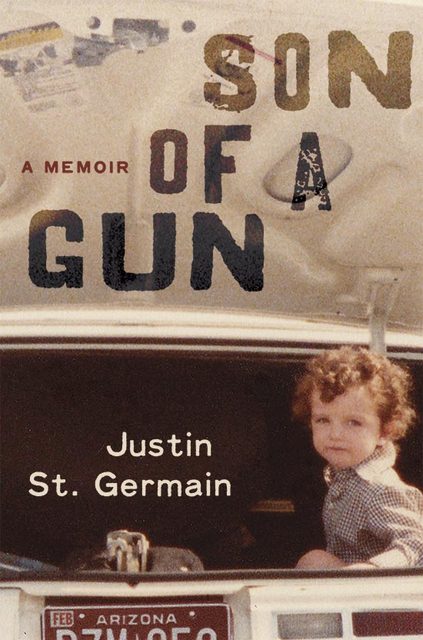

Beyond Legend: Unm Professor Searches For Truth In His Mother’s Desert Murder

Unm Professor Searches For Truth In His Mother’s Desert Murder

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992