The story of 17-year-old Erin Douglass begins on the night her mother dies. The death leaves Erin alone with her father in a cookie cutter subdivision somewhere near Billings, Mont. The subdivision probably has some distinguishing characteristics, Erin probably goes to school somewhere, and her mother probably had a personality, but the author isn’t telling. (Well, it’s not a screenwriter’s job to detail setting and back story).

The novel’s other main thread follows Mo’é’ha’e, a 9-year-old Cheyenne girl who lived 100 years earlier in the same area near the Little Bighorn River. Lacking temporal clues, we can count forward from Custer’s Last Stand and deduce that Erin’s story takes place in 1976. (Leave it to costumes and cars to establish the time frame.)

The two stories intersect when Erin and her father, driving across vast plains to a wedding, detour by the site where her father’s construction company is building a new road. We zoom in to the crew, who are looking at something on the ground. A road grader has broken open the grave of a Cheyenne child wrapped in a rotted blue jacket, with thimbles on all of her fingers. A young Cheyenne crewman, Charlie White Bird, is reverently lifting dirt away from the remains.

Jack Douglass, a “shoot, shovel and shut up” sort of guy, tells the crew to cover up the grave site and not speak of it. A few days later, Erin returns to the work site to see Charlie launching a romance that results in Erin running away from home.

Meanwhile, in the historical thread, Mo’é’ha’e, her mother, uncle and a captive white boy are being forced by the U.S. cavalry into ever more inhospitable terrain after the battle of Little Bighorn.

Stingy with detail elsewhere, Stevens piles on horrifying close-ups from the Indian wars. While Erin’s subdivision floats anonymously, the route followed by Mo’é’ha’e’s group is so vividly described one can feel the hunger and frostbite.

Viewpoints shift oddly from Erin’s first-person story into Mo’é’ha’e’s third person, and into what seems to be Erin looking out from her father and Charlie’s eyes. (A director has to work from inside all the roles.)

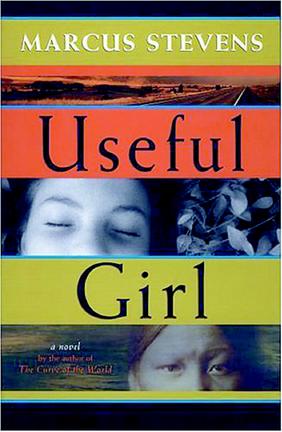

Characters don’t talk a lot, maybe because penetrating our generic humanity to portray a remote culture, getting close enough to the bone to get real, stretches realistically idiomatic language too far. Perhaps the most poignant detail, the source of the book’s title and inspiration, is an opening quote from fellow Montana novelist Thomas McGuane: “He had seen the skeleton of a Cheyenne girl dressed in an Army coat, disinterred when the railroad bed was widened. Her family had put silver thimbles on every finger to prove to somebody’s god that she was a useful girl who could sew.”

As the two stories wind toward a reconciliation of the most basic sort, Erin and Charlie rebury Mo’é’ha’e’s bones, an action that precipitates one more iteration of all the stupid, bigoted tragedies that ever happened.