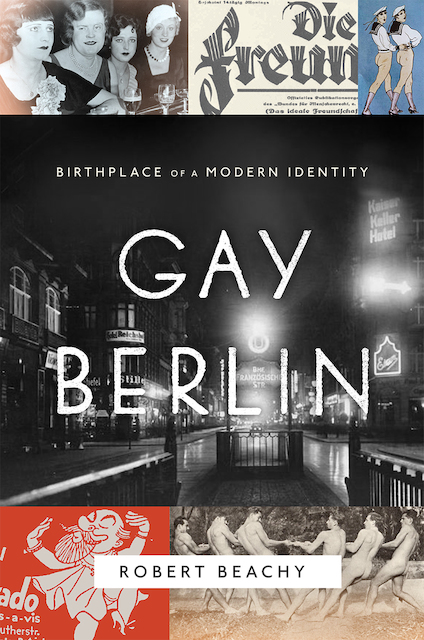

Book Review - Gay Berlin: Birthplace Of A Modern Identity

Book Review - Gay Berlin: Birthplace Of A Modern Identity

Robert Beachy

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Robert Beachy