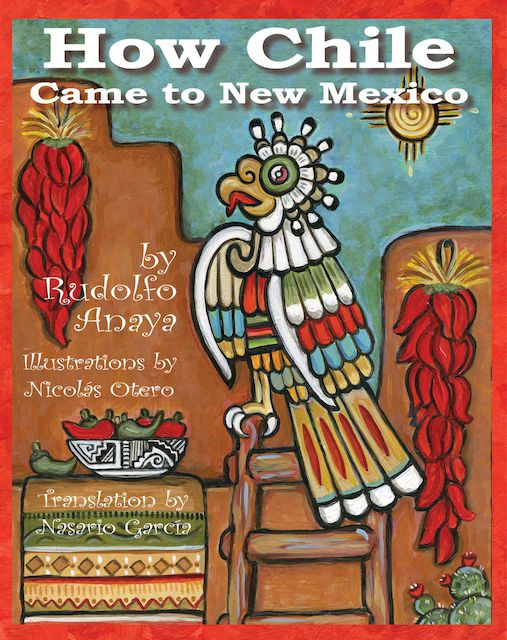

Book Review: How Chile Came To New Mexico / Comó Llegó El Chile A Nuevo México

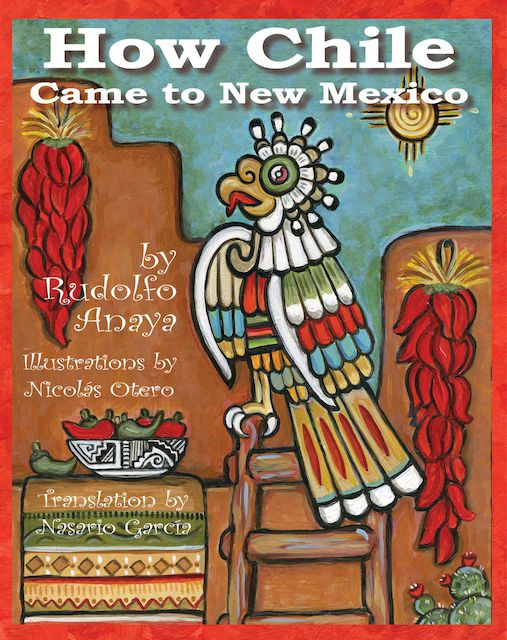

Detail showing those lovely brush strokes

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Detail showing those lovely brush strokes