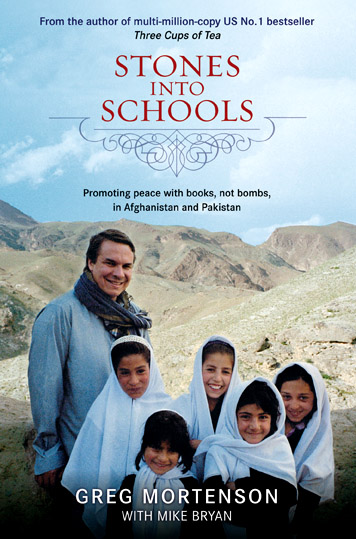

Book Review: Stones Into Schools: Promoting Peace With Books, Not Bombs, In Afghanistan And Pakistan

Greg Mortenson

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Greg Mortenson