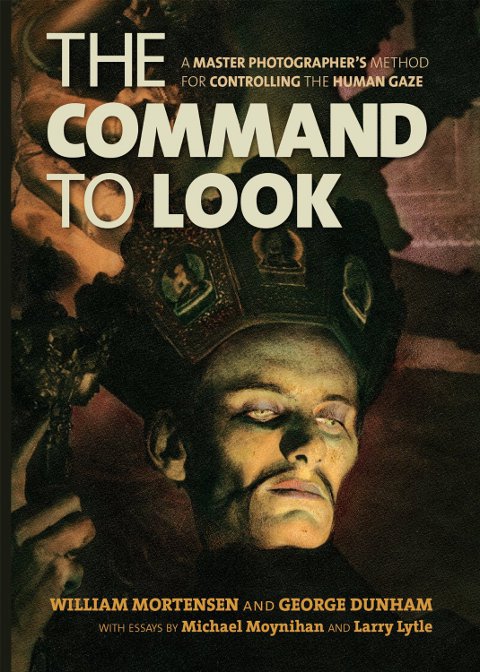

Book Review: The Command To Look

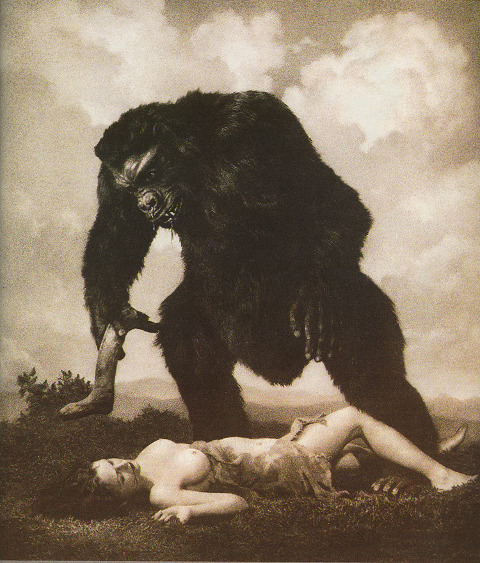

William Mortensen

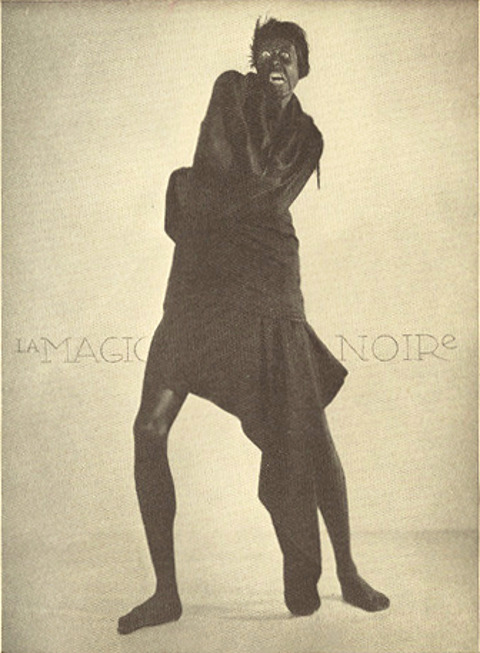

“Black Magic”

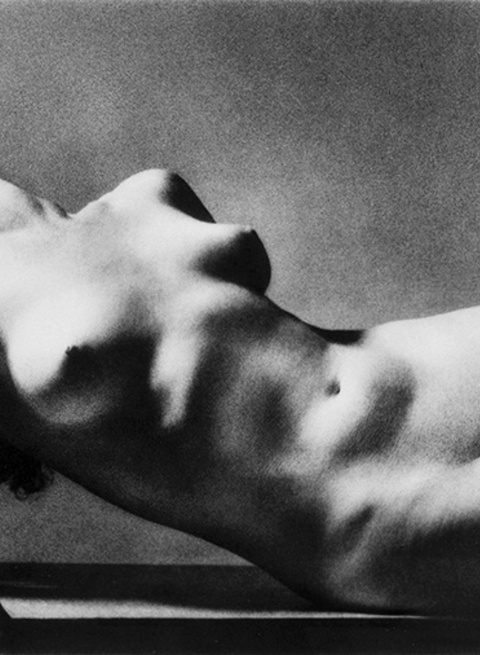

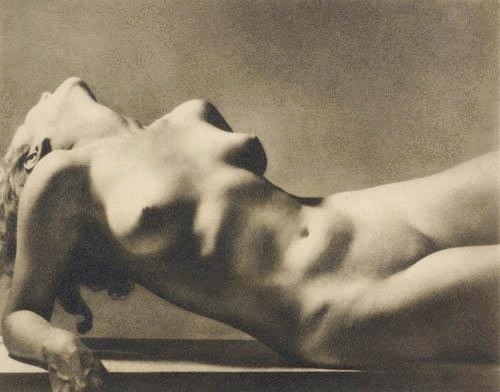

William Mortensen

“L’Amour”

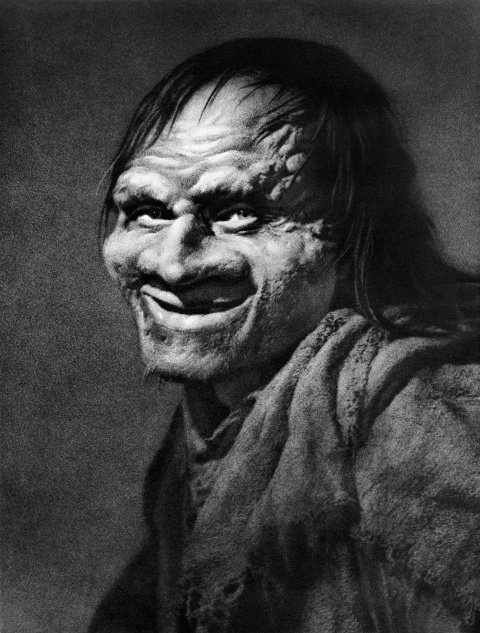

William Mortensen