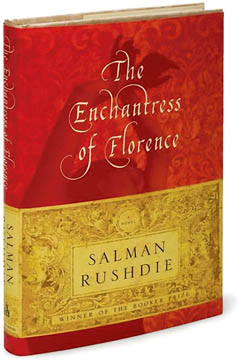

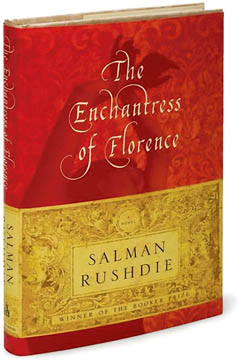

Book Review: The Enchantress Of Florence

The Enchantress Of Florence By Salman Rushdie

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992