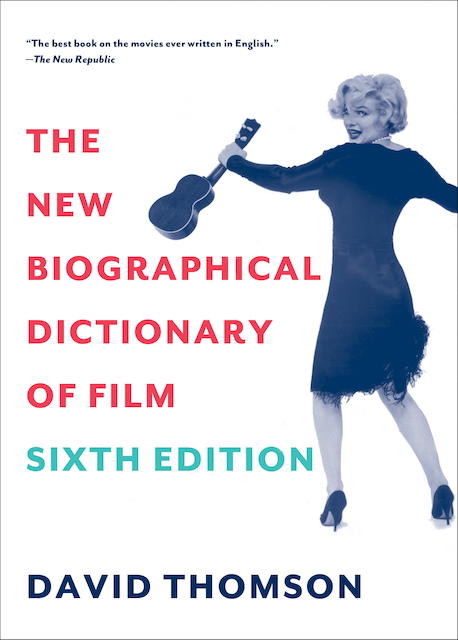

Book Review: The New Biographical Dictionary Of Film (Sixth Edition)

David Thomson allows you to disagree with his opinions—he just doesn’t think it’ll come to much.

photo by Lucy Gray