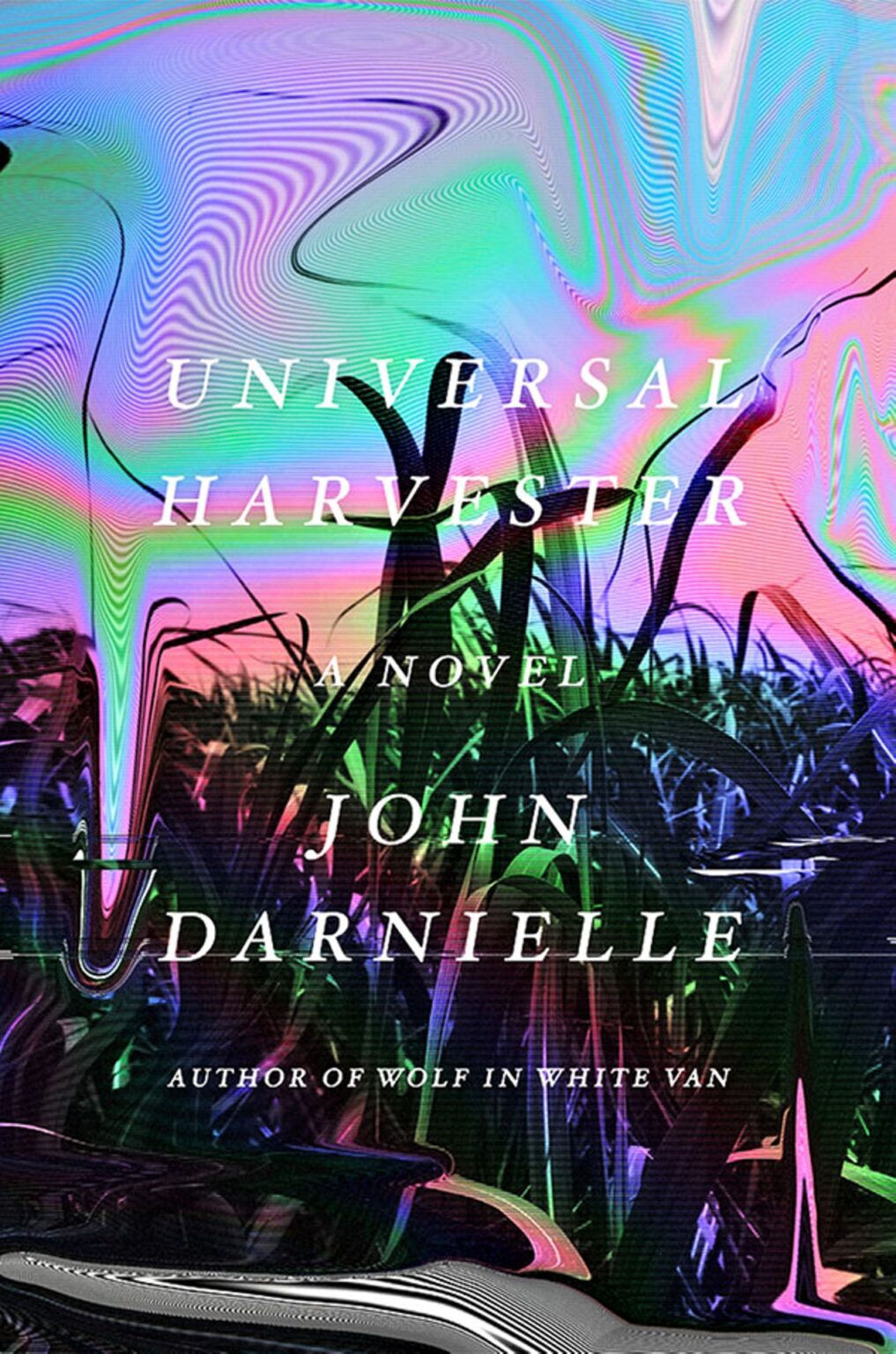

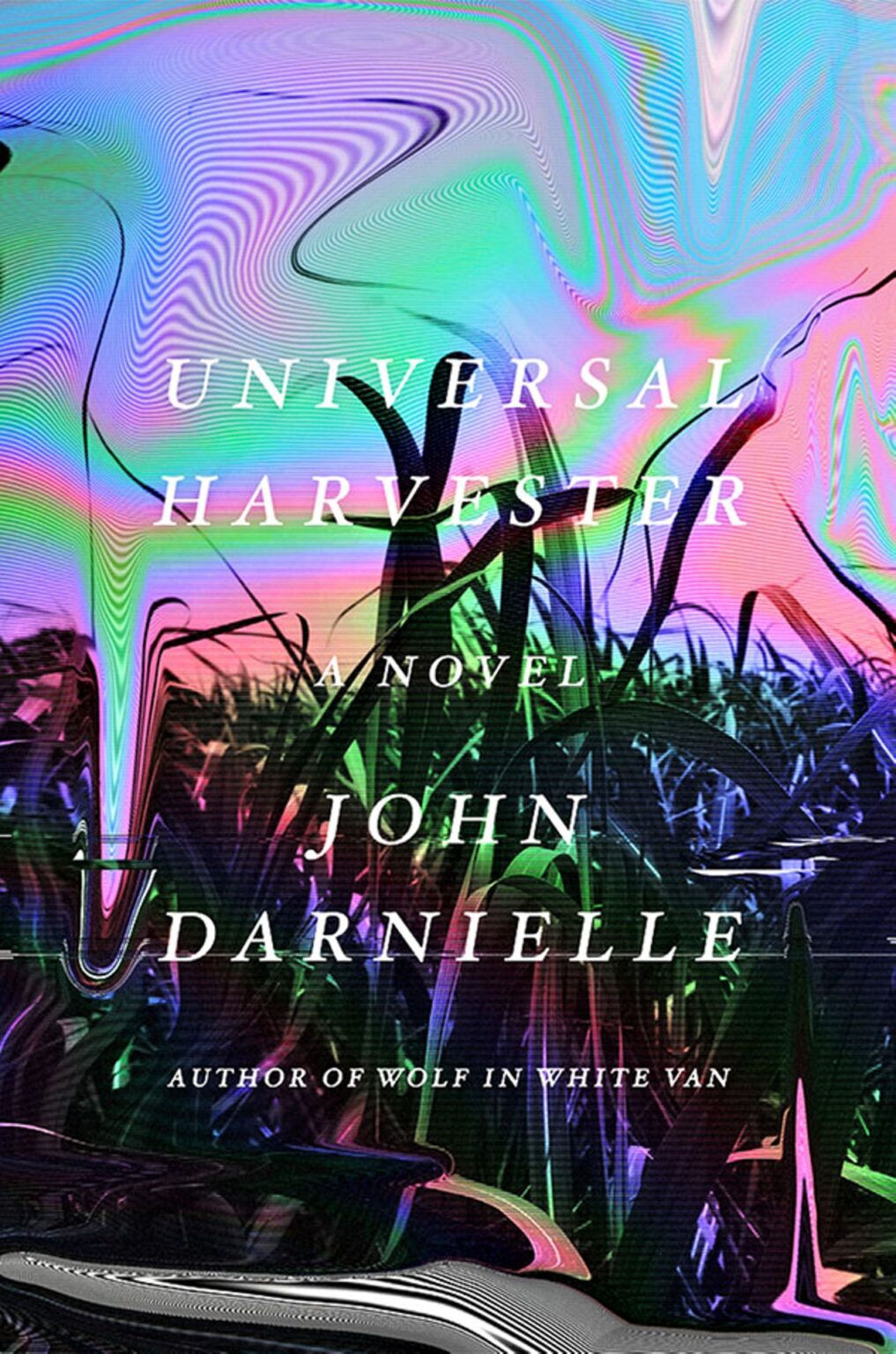

Book Review: Universal Harvester

Universal Harvester Falls Short Of Its Promise

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992