Chabon has continued his campaign against convention well into 2004, publishing a group of books which reveal the breadth of his interests. In addition to yet another anthology from McSweeney's, he has published two installments of The Escapist, a comic strip which grew out of Kavalier & Klay, and now The Final Solution, a novella that takes the classic detective story and gussies it up with all the trappings of a literary novel.

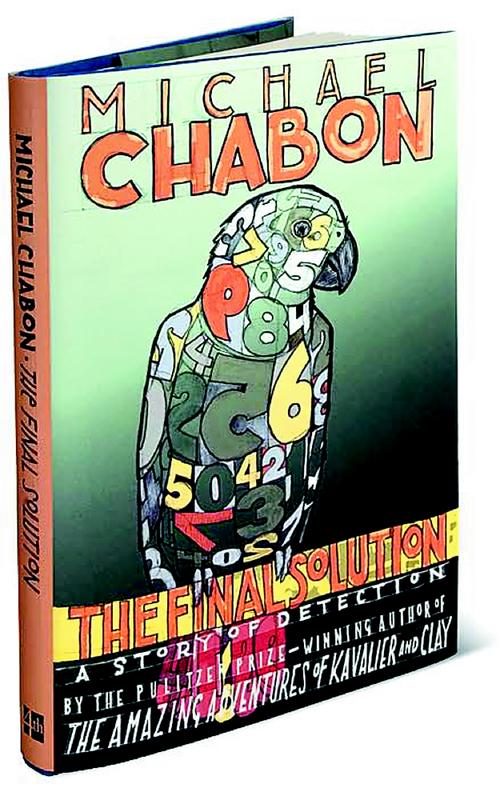

Set in England in 1944, The Final Solution concerns the story of a mute 9-year-old refugee from Nazi Germany named Linus Steinman, who is placed by an aid worker in a boarding house. Shortly after his arrival a fellow boarder turns up dead and Linus' pet parrot, Bruno, goes missing. The two events seem to be related, and in order to solve the mystery Chabon drags Sherlock Holmes out of retirement for one final case.

It takes a steady hand to appropriate the world's most famous detective and make him come alive, but Chabon's got chutzpah to spare. We first re-encounter Holmes in The Final Solution at his apiary, where he has wiled away his retirement. He is proper but a little bit ornery, perhaps too long around the “sonic blank” of his hive. In the pages that follow, we follow Holmes from one scene to the next as he wipes the dust off his skepticism. The man is, after all, 89 years old at this point.

And here is where Chabon shows his greatness. Referring to him throughout as “the old man,” Chabon takes this most mysterious literary figure and gives him a three-dimensional internal life. “Long life wore away everything that was not essential,” Chabon writes in one scene, warming to the theme. “Some old men finished their lives as little more than the sum total of their memories, others as nothing but a pair of grasping pincers, or a set of bitter axioms proven. It would please (Holmes) well enough to amount to no more in the end than a single great organ of detective, reaching into blankness for a clue.”

Although The Final Solution begins in a confusing fashion—it takes 30 pages for the novella's main characters to sort themselves out—it settles down into a deceptively profound tale that, like Kavalier & Clay, reflects on the lengths to which humans will go to crack the inscrutability of the Holocaust's evil.

As in that book, Chabon has taken a horrific event—the unveiling of Hitler's genocidal policies—and approached it from a counterintuitive perspective. There it was the construction of comic books; here it is the production of a mystery. Linus' bird has been sprouting numbers in song and there is speculation that it was giving away the Swiss bank account numbers to Nazi plunder. Not since Julian Barnes' 1984 Booker finalist, Flaubert's Parrot, has a talking bird had this much significance in a work of fiction.

For all his complaints against the strictures of the moment-of-truth story, Chabon is himself quite good at writing this kind of fiction. Indeed, though “The Final Solution” is a detective story, the evolution of its characters mirrors that of literary fiction. Holmes makes one final catch but in doing so realizes that something will always escape him. It's a bittersweet lesson upon which to go out, again, but if this moving little tale is any measure of future demands, something tells me Holmes will be moonlighting in literary fiction again.