Our own little home territory is no exception. Most of the elaborate Native American architecture and art scattered throughout New Mexico has some kind of religious significance. Although the specific function of the buildings in Chaco Canyon might not be fully known, there can be little doubt that the motivation behind their construction was largely spiritual.

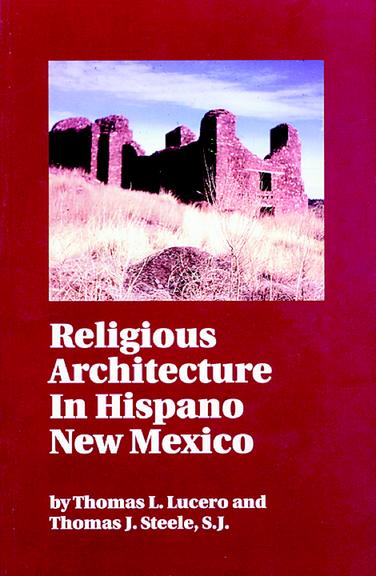

A new book put out by LPD Press, a local outfit based in Los Ranchos de Albuquerque, claims to be “the first major explanation of the architecture of New Mexico's Hispanic adobe churches since George Kubler's landmark publication of The Religious Architecture of New Mexico in 1940.” At the heart of this new book is an intriguing method for classifying New Mexican Hispano architecture based on the increasing complexity of architectural elements, from the simplest residence to the most elaborate mission church.

Of course, to our modern eyes, historic New Mexican adobe churches—even the most ornate ones—are humble affairs. That's a large part of their appeal. One of the best aspects of Lucero and Steele's book, though, is that it succeeds in showing us how majestic these structures would have appeared to those who first viewed them, especially to Native Americans who had never seen anything quite like them.

“Our world is now so filled, saturated, even overwhelmed with images on billboards, in magazines and newspapers, and in the movies and on television,” write Lucero and Steele, “that we must make a concerted conscious effort to realize how relatively empty of art, how lacking in images, was the New Mexico of a century and a half ago.”

Lucero has taught in the UNM School of Architecture and is currently a licensed architect in private practice. Steele is an ordained member of the Jesuit order who has written numerous books and articles on New Mexico Hispano culture.

From a layperson's perspective, the duo is at their best when they're offering up interesting little factoids. Who knew, for example, that European and New Mexican folklore indicates that the air is the domain of evil spirits, and that church bells are designed to cast a sacred sound into the air to dispel these evil forces?

Their book is a short one. It's filled with lots of black and white photographs of some of the finest examples of New Mexican religious architecture—the Las Trampas church on the High Road to Taos, the massive church at Acoma Pueblo, the ruins at Quarai, the Penitente Moradas dotting northern New Mexico. The book also includes plenty of ink drawings of various building plans and architectural features. Despite all these added visual elements, the book's design leaves something to be desired. It just isn't all that attractive. Many of the photographs don't reproduce very well, and the lengthy, inelegant captions are sometimes difficult to read.

Even so, the book is informative, and it offers a classification system that would probably be useful to many amateur and professional enthusiasts of New Mexico's Catholic architecture. Lucero and Steele are also careful to point out that we have very few surviving examples of historical religious Hispano architecture left here in New Mexico. We'd do well to preserve those we have.