Roger Ebert called Keaton “arguably the best actor-director in the history of the movies,” but even that praise is too humble to do justice to Keaton's accomplishments. In the age before the studio system contaminated Hollywood filmmaking forever, Buster compiled his own crack team of film professionals to invent his movies. They ate, drank, smoked and dreamed their films upwards of 18 hours per day. Even though Keaton often didn't take much credit for his own contributions, it's clear from subsequent accounts of the process that he not only accomplished the lion's share of acting and directing but also often came up with plots, created the gags, designed the sets, did the stunts and developed the astonishing cinematic effects that continue to make his films such a pleasure to watch.

Edward McPherson is a writer living in New York. This is his first book. He doesn't have any special expertise that would make him an ideal candidate for authoring a book on Buster Keaton, but he is quite obviously a smitten fan, and that should be enough.

His introduction contains one of the book's finest moments, revealing McPherson's unabashed adoration for his subject. For research, he's decided to attend a Buster Keaton convention in Michigan. People have come from all over the country, and many of them are out and out freaks of nature, the sort of people who've memorized Keaton's hat size (6 7/8), who sport Buster tattoos on their backs, who've gotten married at Buster-specific locations. You know, real wackos.

McPherson isn't quite that far gone, but he expresses an extraordinary amount of empathy for these people. He doesn't know Keaton's hat size, but he can understand how someone would love this stone-faced clown so much they'd want to know such seemingly trivial details.

So, with that in mind, this isn't exactly a detailed work of cinematic scholarship. McPherson has done his research. He's read the right books. He's included the endnotes that any book of nonfiction needs to be taken seriously. But he hasn't made any attempt to write a definitive biography. As he says in his introduction, the book is merely a fan's note written in appreciation for one of the finest artistic talents of the 20th century.

We should be thankful that the subject matter is so infinitely entertaining, because McPherson's writing is often ham-handed. He struggles to nail down Keaton's visual poetry by incorporating bizarre italicized descriptions in the second person of classic scenes from some of the comedian's most famous films. These descriptions are awkward and largely pointless.

When he isn't adopting such pretentious gimmicks, McPherson does a decent job of describing individual films, but the really juicy bits in the book are the biographical details he's compiled, largely from other books, many of which are currently out of print. He does a good job, for example, of covering Keaton's days as a young vaudeville star, his dad's violent alcoholism, his family's efforts to circumvent child labor laws, and the early stirrings of comedic genius evident in Keaton's preadolescent gags at the expense of his friends, family and random strangers. (Some of these pranks are so elaborate they're difficult to believe. The machinery Keaton created to make all four walls of an outhouse collapse, exposing the occupant, pants down, squatting over the hole, is one particularly devious example.)

In 1917, Keaton finally busted into the movies. That year the comedian Fatty Arbuckle hired him to collaborate on a series of two-reel comedies. From there, Keaton quickly springboarded into international stardom. It's amazing the free reign he had to make movies exactly the way he wanted through most of the '20s. It's just as remarkable how his talent was crushed once he signed with MGM and had to begin making films inside the hyper-restrictive corporate studio system.

In the early '30s, Keaton's career tanked, along with his marriage and his relationship to his children. These are the dark years of alcoholism and sanitariums. It's unbelievably depressing stuff, but it makes for a great read.

Thankfully, Keaton eventually managed to pull himself out of his cycle of self-destruction and rebuild his life. He never played starring roles in big budget films again, but he had a second career in television and small bits in films that lasted all the way up to his death in 1966.

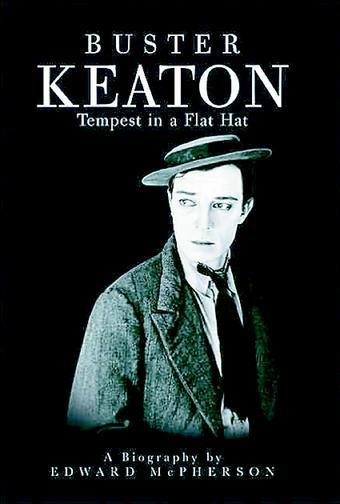

McPherson isn't a great writer, but Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat is entertaining, and he does succeed in explaining Keaton's continuing appeal to modern viewers. In film as in life, the acrobatic little clown persevered through crisis after crisis to eventually emerge triumphant. This endurance is what made Keaton so endearing, both as a fictional character and as a real person. From the very first film, he had a way of making the impossible look as simple as breathing.