Hall's protagonist, Cy Parks, finds himself among these throngs after escaping his mother's creepy boarding house in Morecambe. He leaves behind an apprenticeship with a brutal tattoo artist and sets up shop in Coney Island, where he hears more freak stories than a SoHo hairdresser. Hall is a richly lyrical writer, and her prose blooms to a fat bouquet here in its attempt to capture New York in the '30s. Cy finds that the ecstatic business of New York is brought into his tattoo parlor. He meets women who want sex after the sadistic pinch of his needle, and falls for one: a tight-roper who wants her body covered inch by inch with green-rimmed eyes. How's that for turning the male gaze on its head?

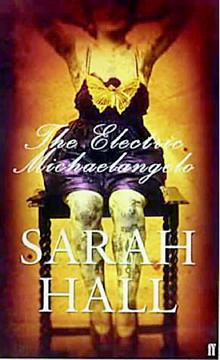

As this image might hint, The Electric Michelangelo occasionally suffers from some over-determined themes—of what we do with pain, of how the body is a canvas for that battle. Still, such slips aside, it's hard not to admire Hall’s earnest desire to push readers outside the mainstream. In this curious second act she moves beyond England in a story that plumbs readers' metaphysical—and visceral—threshold for pain.