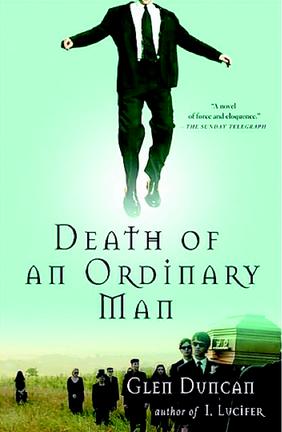

Duncan’s narrator is Nathan Clark, a father of two who, at the beginning of the action, floats ethereally over what he comes to realize is his own funeral. Passage into the afterlife must leave one with a wicked hangover, for it takes Nathan nearly 60 pages to realize he will never, ever speak to his wife again. Even then his reaction is curiously muted: “Suddenly, he missed her, their shared history. The way they remained tuned to each other across a room full of people.”

In moments like this, Duncan’s novel comes dangerously close to sounding like a Michael Keaton film in the making. After all, asking people to imagine they are dead—and what regrets that would entail—can feel cheap and emotionally manipulative. Who won’t have misgivings? Duncan is better off when he sticks to the curiosity factor. What is it like, most of us are dying to wonder, to live with no tomorrow and no yesterday, no here or there, no bodily corpus to weigh us down? Eerily and occasionally with a certain degree of beauty, Death of an Ordinary Man shows us what that might feel like.

It is through these sensations that Death of an Ordinary Man becomes more than just an ordinary “what if” kind of novel. As it turns out, Nathan can not only pass through walls but he can float into the heads of his loved ones and hear their thoughts as they mourn his passing.

Over the course of this novel, he becomes intimate with his family in a way he’d never found possible in life, and relives the death of his first child in the process. It is a painful, heartbreaking journey, made all the more so by the fact that the knowledge he gleans from this ghostly privy can never, ever come to any use.