Giving Names To The Land

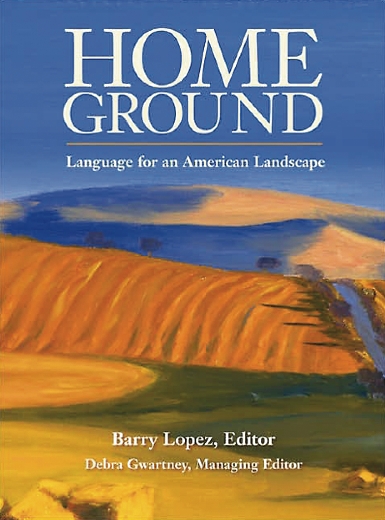

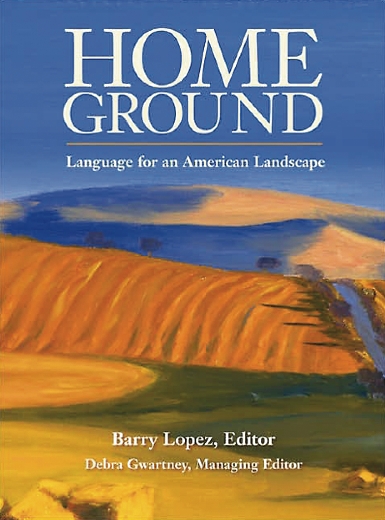

Barry Lopez’ Home Ground: Language For An American Landscape

Barry Lopez

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Barry Lopez